Flashcards for dead hands

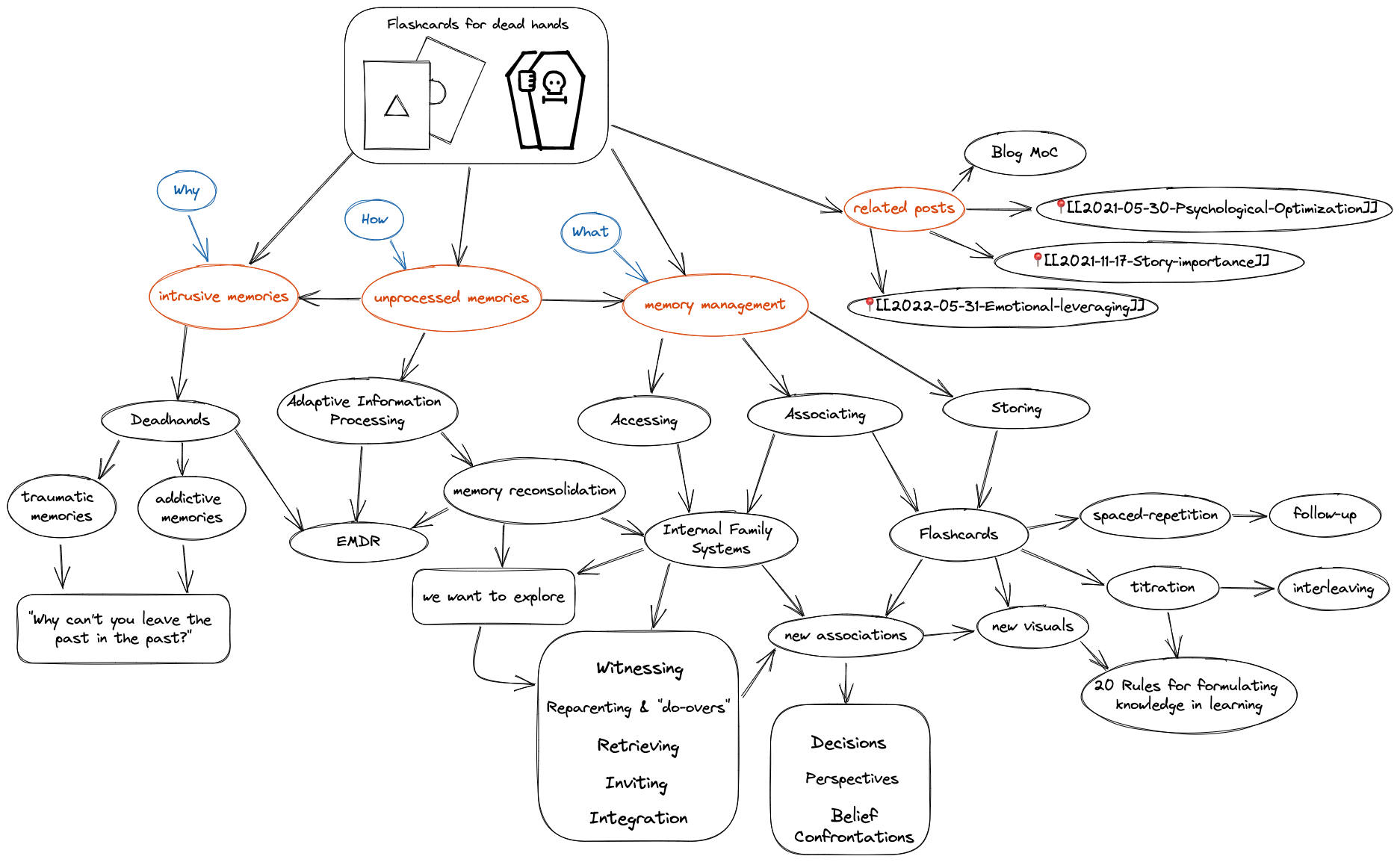

Using flashcards to process and store intrusive memories.

Flashcards for dead hands

TLDR

- Intrusive memories signal unprocessed memories

- Unprocessed memories are the roots of many mental health problems.

- To reconsolidate intrusive memories, carefully go to them, not away.

- Internal Family Systems surfaces info for memory reconsolidation.

- Notes and flashcards aid retention of IFS info for reconsolidation.

- Flashcard guidelines benefit memory reconsolidation efforts.

Overview

Intrusive memories

Dear Young Tim,

Why can’t you leave the past in the past?

Over time, this question will bring much irony to our life. When these words first slammed into our eardrums like a pot thundering to the floor, we rejected them outright. Immediately, we rejected the premise we believed the question was based on. After all, knowledge is power, right? Why would we want to forget what we know of the past? We then rejected the question itself as a distraction. Instead, we opted to “delve deeper” by focusing on the question’s motivating problems.

While not incorrect, the ironies would come months later, after the motivating problems were indeed firmly placed in our past. First there was the loss of appetite and pounds. One pound, two pounds, ten pounds, and more. For some time, flashbacks of painful past experiences would rob us of preparatory time and desire to eat. Not to be a “Debbie Downer” forever, we eventually upgraded to more positive problems. Here, pleasant memories would greet us upon waking and usher us daily onto the dance floor for an intensely dysregulating waltz of happy -> sad -> angry, happy -> sad -> angry. So, despite our initial reactions and for different though related reasons, we again asked “why can’t we leave the past in the past?”

Merriam-Webster defines a “dead hand”

as “the oppressive influence of the past.”

Whether pleasant or unpleasant,

intrusive memories

have served as nature’s faithful dead hands in our life.

These intruding memories may be thought of on a linear spectrum,

with traumatic (i.e. intensely unpleasant) memories on one end

and appetitive or addictive (i.e. intensely pleasant) memories

on the other end.

Both ends lead to dysfunction, though via differing mechanisms.

Merriam-Webster defines a “dead hand”

as “the oppressive influence of the past.”

Whether pleasant or unpleasant,

intrusive memories

have served as nature’s faithful dead hands in our life.

These intruding memories may be thought of on a linear spectrum,

with traumatic (i.e. intensely unpleasant) memories on one end

and appetitive or addictive (i.e. intensely pleasant) memories

on the other end.

Both ends lead to dysfunction, though via differing mechanisms.

Unprocessed memories

One therapy modality that has proven useful in treating problems related to intrusive memories is EMDR. In randomized controlled trials, EMDR has helped traumatized individuals and individuals with addictions. Underlying the mechanisms of benefit in both situations is a common understanding that “unprocessed” memories lead to both types of intrusive memories. The sensations accompanying the intrusions then drive extreme emotions, beliefs, and behaviors. As put by Solomon and Shapiro (creator of EMDR),

Problems arise when an experience is inadequately processed.

Shapiro’s AIP [Adaptive Information Processing] model (1995, 2001, 2006)

posits that a particularly distressing incident may become stored in state-specific form,

meaning frozen in time in its own neural network,

unable to connect with other memory networks that hold adaptive information.

She hypothesizes that when a memory is encoded in

excitatory, distressing, state-specific form,

the original perceptions can continue to be triggered

by a variety of internal and external stimuli,

resulting in inappropriate emotional, cognitive, and behavioral reactions,

as well as overt symptoms (e.g., high anxiety, nightmares, intrusive thoughts) (p. 316).

[…]

Pathology is viewed as unprocessed memories, […] (p. 318).

Similarly, other EMDR researchers would later note (p. 4)

it is not the positive or negative quality of the feelings that is important in creating a state-dependent memory but the intensity of the feelings.

In both situations, the explanation of unprocessed memories begs the questions of what is a processed memory and how can one process memories?

As described by EMDR therapist Laura Paton,

A processed memory will generally be something that you know has happened,

don’t regularly think about, and when you do,

it doesn’t have any emotional charge associated with it,

and you feel no need to bring it up regularly

or think about it for a prolonged time.

According to Solomon and Shapiro (p. 320), one key mechanism in processing memories is associating otherwise disjointed fragments of memory. Specifically, (re)processing a memory involves associating:

- the intrusive memory ‘image’

- extreme beliefs related to the memory

- functional beliefs you instead wish to relate to the memory

- the current emotions related to the memory

- the current physical sensation related to the memory

These associations are thought to facilitate “memory reconsolidation,” wherein one updates the information and the form of the information accessed with a memory. For example, we update emotion(s) and emotional strength of the memories, beliefs based on the memory, and experienced sensations (or the lack thereof). The end result is a processed memory and its accompanying symptom relief.

As described by Ecker et al. (p. 89), memory reconsolidation roughly happens by

- accessing the disturbing memory and its explicitly associated beliefs, emotions, and sensations

- providing an alternative, less disturbing experience alongside the memory (such as with bilateral stimulation in EMDR desensitization phases)

- associating new, desired beliefs with the accessed, disturbing memory

This memory reconsolidation process is also believed to lie at the root of how the Internal Family Systems (IFS) model of therapy works, as pointed out by neuroscientist Dr. Frank Anderson in “Transcending Trauma: Healing Complex PTSD with Internal Family Systems Therapy” (ch. 24, #The Science Behind The Healing). This connection offers us guidance for synergistically combining some of our pre-existing efforts in emotional regulation and memory management. We gain increased hope of efficient and consistent progress towards memory reconsolidation and freedom from intrusive memories.

Memory management

What and why

We use the term memory management (with people) to refer to the control and directing of what we remember and how we remember it. For example, two explicit memory management techniques are making and using notes and flashcards. In previous posts, we’ve recommended these practices for numerous reasons, including:

- remembering facts and thoughts that we consider important

- remembering our organization of important facts and thoughts

- associating images and sensations with memory of facts

(e.g. associating physical sensations to names of yoga poses) - and streamlining our efforts to produce and remember new thoughts

Ultimately, we manage our memory to improve critical parts of our life. Because whether or not we reconsolidate our intrusive memories directly impacts our current and future emotional regulation (i.e. a critical part of our life), intrusive memories and the actions we take on them are automatically critical components in our memory management efforts. We therefore stand to greatly benefit from explicitly noting, acting upon, and strengthening the connection between memory management and emotional regulation. We’ll start by considering our practices and perspectives of emotional regulation and how those impact our memory management. Then, we’ll look at what emotional regulation benefits we can glean from our memory management practices and perspectives.

Internal Family Systems

In previous posts we’ve written about using IFS techniques for and perspectives on emotional regulation. These perspectives provide a window through which we can view intrusive memories— a view that is complementary to that of Shapiro’s AIP model. The IFS view of intrusive memories then informs our memory management stance towards the intrusions.

Similarly, memory reconsolidation and the AIP model complement IFS’ view of unburdening. Here, reconsolidation motivates memory management interventions at each stage of IFS’s unburdening process.

Views

First, intrusive memories show up as both “burdens” and as “trailheads” in Internal Family Systems. For instance, as described by Bonnie Weiss (a therapist and author, certified in both EMDR and IFS),

a burden is an extreme feeling, memory [emphasis added], energy or belief about oneself or about the world that a part has taken on as a result of childhood trauma, a specific incident, a relationship, or another painful situation. The burden is not natural to the part and therefore can be released.

—Self-Therapy Workbook: An Exercise Book For The IFS Process (p. 107)

From this definition, a logical next step is to use the IFS “unburdening process” to release the burdens, i.e. the intrusive memories. As suggested by its name, the unburdening process focuses on “getting rid of something.” However, despite wishing for a fast jettison, unburdening is actually a long journey. It begins with making contact with the parts of our mind holding the burdens. We make contact by exploring “trailheads.”

Weiss writes that

A trailhead is an experience or difficulty in your life that will lead to interesting parts if you follow it. It can be a situation or person that you react to, an emotional or bodily experience, a pattern of behavior or thinking, a dream, or anything else that indicates one or more parts to explore. IFS calls it a trailhead because it is the beginning of a trail that can lead to healing.

—Self-Therapy Workbook (p. 17)

From here, we note a duality in our intrusive memories. Certainly, the intrusions are burdens to be released. However, they are also trailheads to be explored, rather than avoided or suppressed. IFS’s trailhead terminology highlights investigation of intrusive memories in the reconsolidation process. This investigative focus balances the negative judgement connoted by terms such as “intrusive memory”, “burden,” “pathology,” etc. The negative connotations of such words and concepts may increase the likelihood one seeks relief by intuitively staying away from the intrusive memories rather than examining them explicitly, with care and compassion.

Accordingly, in the long-term, we won’t chronically respond to intrusive memories with “just get over it” or “stop thinking about that.” To “get over” intrusive memories of our past, i.e. to finally “leave the past in the past,” we want to explore these memories. Specifically, we want to explore them in ways that result in memory reconsolidation. Some such ways include IFS’ unburdening process, EMDR’s phased approach, etc.

Brews

Above, we noted that memory reconsolidation has three core steps. In shorthand, they are memory access, memory “mismatch”, and memory association. To enable these three steps, there are preparatory stages to gather needed information (Ecker et al., pp. 90 - 91). For example, what’s the memory, what’s a less disturbing experience, and what are the desired, new associations? This is where IFS’ unburdening recipe comes in. The unburdening process incrementally takes one through the memory reconsolidation steps, surfacing the information needed to progress through the steps in one extended sitting.

The information from unburdening is naturally suited for memory management, e.g. for notes and flashcards. In particular, unburdening surfaces a huge amount of information. This deluge motivates explicit management, if only to prevent slowdowns from information overwhelm. For memory reconsolidation, we ideally want to remember all this information at will and at speed.

As informed by the discussion in Transcending Trauma (ch. 24, #The Science Behind The Healing), the information we’ll want to capture is as follows. First, we use IFS’ 6F’s to begin exploring a given intrusive memory. Here, we want to collect the full range of symptoms that arises with memory access. Such symptoms include activated parts of mind, our beliefs, emotions, sensations, and actions. Then, we want to capture and organize the details of the intrusive memory. These details come from one or more rounds of IFS’ witnessing.

With the ability to re-access the memory, we’ll next want information that will allow us to simultaneously provide an alternate, less disturbing experience. IFS supplies this information through its imaginative, do-over part of reparenting. As before, we’ll want to store such information, so we can later access it on-demand. The do-over provides the mismatch experience that disconnects the intrusive memory from its original, burdensome reactions. Once disconnected, we can associate the intrusive memory with desired, “adaptive information.”

The final reconsolidation step links to adaptive information by pairing the original intrusive memory with new, ‘disconfirming [experiential] knowledge’ (Ecker et al., p. 91). These new learnings are provided by the IFS steps of

- reparenting where, in the present, we assess and decide how to meet the needs of the parts of us that are activated by the intrusive memory

- retrieval where we can update and confront outdated beliefs, i.e. beliefs that no longer benefit us

- invitation where we link new emotions with the intrusive memory (via association with our parts of mind activated by the intrusive memory)

- integration where we choose new behaviors to associate with the various parts of our mind activated by the intrusive memory

In all such steps, we want to actively manage our memory of our emergent scenes, internal dialogue, and associated feelings. Again, such management may be external as with notes as well as internal through tools such as flashcards.

At this point, we have all of the information needed for the memory reconsolidation process and for IFS’ celebratory unloading. Afterwards, the only remaining tasks are to follow-up on the unburdening and to verify that one’s symptoms have disappeared.

As described in Transcending Trauma (ch. 24, #The Post-Unburdening Process)

Dick Schwartz says it can take about three to four weeks before an exile appears to integrate back into the system. Again, we don’t exactly know what’s happening in the brain during this process, but I sense that it has something to do with reinforcing the newly reorganized neural network. […] I recommend that clients briefly check in with their unburdened part every day for about three to four weeks, as Dick Schwartz has advised.

This follow-up process most closely relates to existing aspects of our memory management practices, so we’ll turn our attention there next.

Flashcards

Spaced-repetition

In managing our memory, we are crucially concerned with reinforcing and ensuring function of the neural networks that allow access to particular memories and learnings. Spaced-repetition is our key practice for memory reinforcement. It is one of the most effective methods for maintaining associations in memory over time. This technique is the raison d’être we’ve recommended using flashcards with Anki. Anki uses spaced repetition to schedule its reviews.

Here, we can directly apply spaced repetition by creating flashcards for the scenes, sensations, emotions, and beliefs from our unburdening and memory consolidation processes. Such a practice is intensive at first (as with daily check-ins for a month post-unburdening), but long-term maintenance of healing and freedom from intrusive memories seems to be a fair trade.

Titration

Beyond the spaced follow-up to our reconsolidation efforts, other common memory management techniques also promote beneficial emotional regulation practices. For instance, consider the “20 rules of formulating knowledge in learning.” This is an iconic set of guidelines for using flashcards to manage one’s memory. This guide advocates minimizing the amount of information per flashcard. In conjunction, it encourages using many atomic flashcards to collectively represent complex information.

Using atomic flashcards ensures that we only access small bits of the intrusive memory and its related information. Each bit is less likely to cause emotional dysregulation than the original intrusive memory as a whole. Such small and contained access to one’s memories is precisely recommended to psychologically titrate (p. 269) traumatic memories, i.e.

prevent [people] from becoming so engaged with the traumatic material that they become overwhelmed by the powerful images and stories.

As with EMDR, titration soothes traumatic memories, addictive memories, and emotionally dysregulating memories generally.

Visuals

Lastly, we liberally use visuals when creating flashcards for memory management, (see rule 6 of the 20 rules–“use imagery”). In particular, we associate new, hopefully less-disturbing visuals, with the intrusive memory. This connects the “frozen in time” neural network to other memory networks (such as those holding the memory of our flashcard images). Here, note that words and images activate related but distinct networks / parts of our brain. Accordingly, our new visual connections complement associations formed through verbal, psychoanalytic talk therapy. Such stimulation of our visual processing, while accessing intrusive or disturbing memories, is also a major part of EMDR therapy and art therapies.

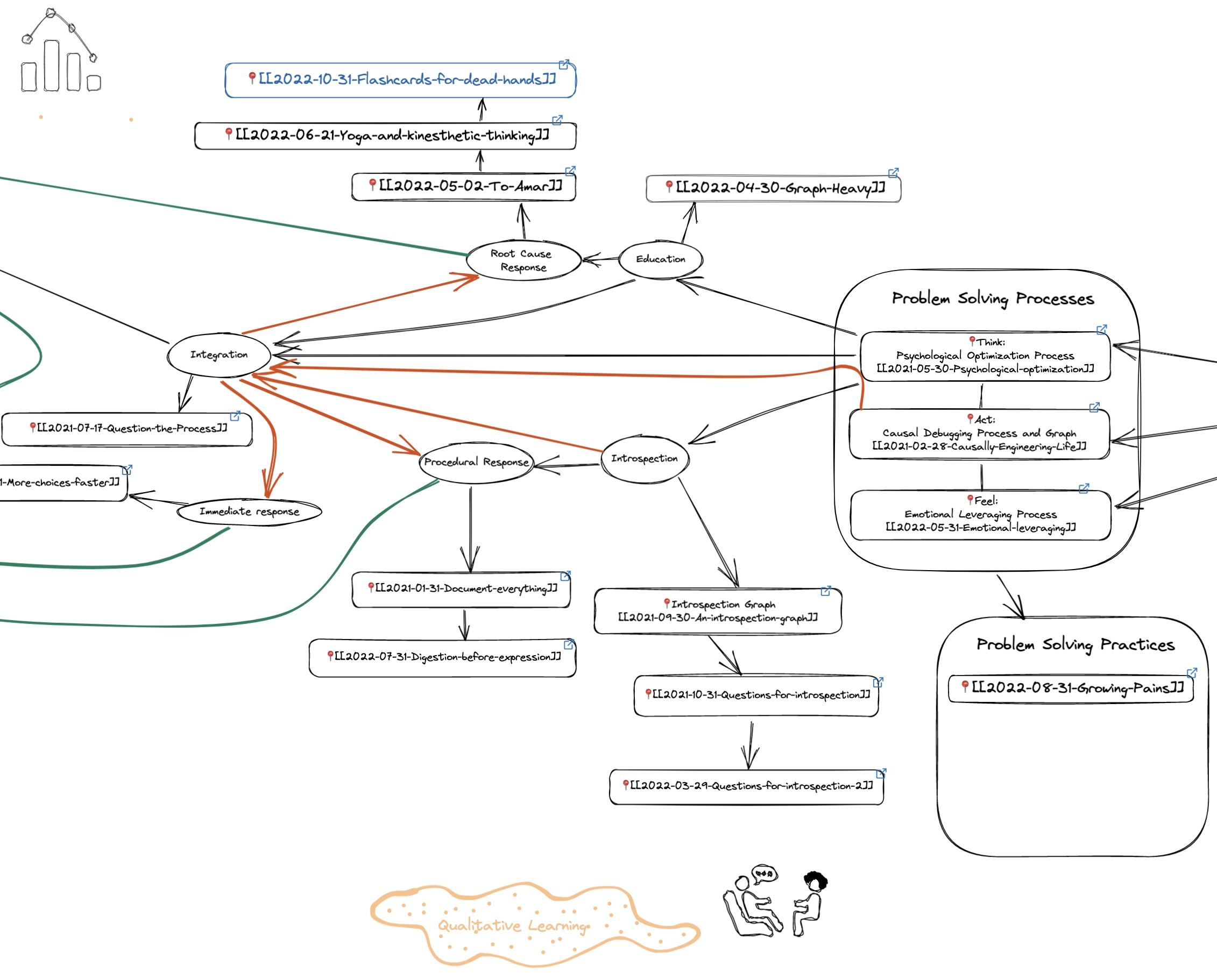

Related posts

The bigger picture of this blog’s contents is shown below, cropped to the subgraph of posts that’s most relevant now.

Our current post details how to fundamentally change our recall of disturbing memories. As such, we attach this post to the root cause response category, and we highlight it in blue. Our categorization connects this document to earlier posts detailing fundamental change. E.g. change in the sensations we experience and in the actions we take.

Besides similarity of function, this post also concretizes some of our earlier thoughts. For instance, in Psychological Optimization, we speak of a need for education and introspection in dealing with specific traumas. Our current post provides a (personally) accessible introduction and link to further educational material for addressing traumatic memories. Additionally, we discuss and link to guidance for introspecting and productively exploring disturbing memories.

Relatedly, Story Importance went beyond investigating traumatic memories (as with introspection). We suggested “revising our stories and models of how the world works.” However, though we spoke of worldview revision in general terms, we gave no implementable process for revision. Our current post details a practical process for worldview revision through memory reconsolidation.

Finally, we continue a line of thought that “fleshes out” ideas for addressing general emotional dysregulation. In particular, Psychological Optimization noted the need to focus on emotional (dys)regulation. We elaborated on this thinking with Emotional Leveraging. There, we outlined how we can regulate ourselves in the face of strong emotions that fail to be ultimately helpful. With our current post, we extend our Emotional Leveraging thoughts in two ways. We provide details and pointers to components for the unburdening stage, and we broadly contextualize the unblending and unburdening processes through memory reconsolidation.

So Young Tim, this is what I wish I told you long ago. To “leave the past in the past,” we need deliberate and extensive efforts in memory reconsolidation and memory management. Until then, the dead hands will ever remain in our present.

Till next time,