Heavy on the graphs

On the use of graphs and mindmaps for mental organization

Heavy on the graphs

Dear Young Tim,

We both know how we hate the feeling of constant pressure behind our ears— the radiating and throbbing throughout our skull, our sunken head, and our collapsed shoulders. At those all too common times, our unplanned bodily tension mirrors and points to the deluge of thoughts racing through our mind, sweeping us off our feet and taking our breath away, for good or for ill. This is overwhelm embodied, and it IS a problem. Most basically, chronically elevated stress harms and kills.

So, what are the underlying issues leading to this overwhelm? Centrally, it’s information overload: I have too many sources of input (ESPECIALLY from my own thoughts1) relative to the effectiveness of my current methods for making sense of, remembering, and leveraging this incoming information. Similarly, problem overwhelm heavily overlaps information overwhelm. When there are many problems, I have difficulty holding all of them (and their relevant information) in my head at once for joint consideration, analysis, and prioritization.

Informational overload is not a new experience for us, though its intensity may be greater now than in the past. Most recently, I noted this problem in January’s post, where I suggested writing out our problems, so they could be held on paper rather than in our minds. In similar fashion, a year ago, I suggested writing out our thoughts in general. In both such cases, writing has been helpful but insufficient. We transformed our source of overwhelm from our thoughts to written documents. However, these documents still have to be read, processed, and internalized or utilized.

Fundamentally, we need more than another information source or medium. We need a way to organize the information we have, to make sense of what we know of the world. We need a way to make clear what we know, to convey the big picture to ourselves, and to help us retrieve desired information on command in the future. What we need is a map of our knowledge, or more precisely, many such maps. In much the same way that a series of geographical maps (at different zoom levels and for differing purposes) organizes the complexity of the real world and makes it legible enough for us to productively navigate it, a series of mind maps can help us organize and navigate the mental landscape of our thoughts.

Of course, one might ask why do we need to organize our thoughts? Why is capture plus digitally-enabled search and need-based usage not enough? There are at least three reasons why organizing our mind(‘s thoughts) is useful, beyond capturing and searching. First, in the simplest of terms, we want to be mentally ordered, not mentally disordered. This helps us act effectively to meet our needs. The process of organizing our mind IS bringing order to our mind.

Secondly, great organization comes at great cost, but it brings great speed. See the notion and organizational principle of mise en place, used by world-class chefs to enable the rapid production of complex meals. As stated in December 2020 one of our life goals is to move fast forever, and this requires that we think fast too, hence the wisdom of organizing our mind.

Finally, we want not just to think quickly and to be able to find information when needed. After all, it becomes annoying to open one’s phone or computer to search repeatedly, even if we can find what we’re looking for. It is much more efficient to simply know or remember something. Here, mind maps are also helpful, as they engage our visual and spatial memories, in addition to our verbal memory.

So, how can we become mentally organized? At its core, I believe we can mentally organize ourselves as follows. (Note, I believe that self-education will generally include these steps as well).

- First, think externally (i.e. on paper and / or on computer). This aids storage, retrieval, and editing of one’s thoughts.

- Secondly, think visually and relationally, in addition to verbally. That is, make graphical diagrams—images consisting of nodes and edges, such as mind maps, concept maps, and the like. I’ll refer to all such images in this post as mind maps. This is where we make sense of how our knowledge relates to other information, where we summarize information for comprehension, and where we can place images that aid our future recall.

- Finally, think repeatedly and stably. Internalize our mind maps by repeatedly recalling portions of the map, such as via image occlusion with Anki. This will ensure we have mental access to the mind map and all portions of it, alongside the underlying knowledge it contains.

After these three steps we will likely find ourselves at peace with whatever information we just mapped.

So what does an example of such mental organization look like?

Consider this blog as a collection of letters,

filled with advice that I hope is useful,

to both younger and future me.

Here, as in all cases,

I need to know what information is in the blog

in order to benefit from it2.

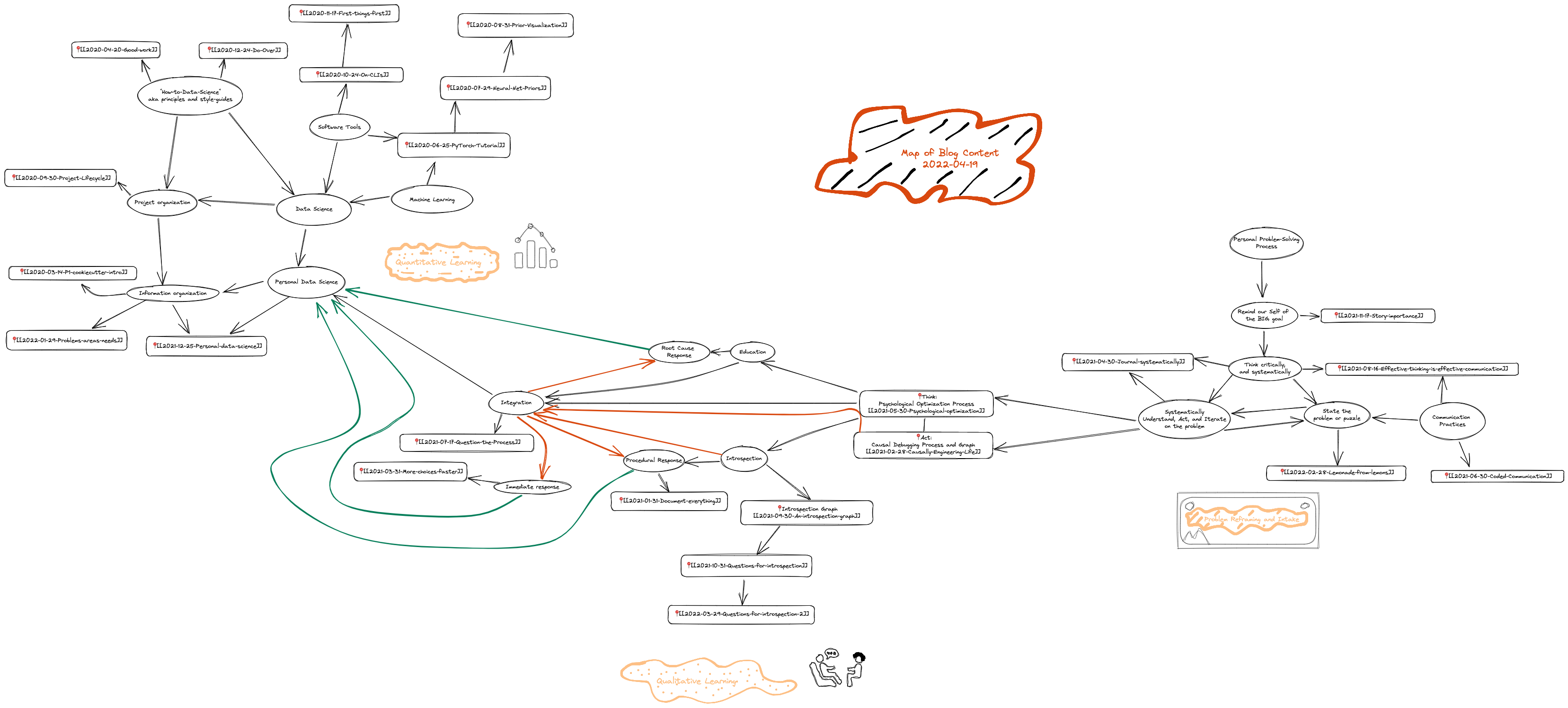

The mind map below depicts one way of organizing this blog’s posts

(except for this post itself, which is a descendant of the title node).

Please do open the image in another tab to explore a larger version of it.

While I plan to detail this mind map in future posts, I will state the high level story here. In the beginning, we started off discussing data science and our thoughts on its practice for quantitative learning. Then we shifted to thinking about processes for qualitative learning, and our focus has been alternating with problem-solving in general. There will be more to come on this in the future, but from our outline of a story about the blog so far, we can further discuss the nodes in each story (or mind map) section, and we can discuss how each post impacts our understanding and our actions.

Hopefully this example gives an idea of what is possible, and I hope this and many other mind maps help us reduce our incidence and intensity of information overload.

Till next time Young Tim,