On problems, areas, and needs

Benefits of linking problems to areas of life and personal needs.

On problems, areas, and needs

The lesson

Dear Young Tim,

Happy New Year! Thanks so much for getting us here.

I know it’s 2022, but can we think back for a second to 2008? Back to that primordial “whoop!” we let out in the parking lot? Back to when Darren and Andrew put us on? Back to when they saw us struggling to learn to skid: struggling to unweight the rear wheel.

We took notice when we saw the rain clouds.

This was the kind of storm that made people seek shelter.

Typical of us, we instead strapped on our rain jackets and rode out.

Mobbing in the 7-Eleven parking lot,

we ate hotdogs, drank slushies, and skidded circles

with freedom that boys fresh out of high school feel.

To be honest, I didn’t want to ride in the rain. I hated the cold and soaking environment. However, where I saw problems, this time—they saw promise: a promise of a path that while harsher in bearable manners, was easier in all the ways I needed. So we weren’t initially fans, but boy did we grow to love it. Once Darren and Andrew hit their first 360’s, we were sold. It was playtime.

And it worked. That first yell—that first glimpse of success. A 270-degree skid in the parking lot, and I was set forever. Our fingers were bone-chilled, but our hearts were warmed! We would skid at will, on any surface, any time.

All this was possible once we knew what success felt like, even if artificially induced. Succeeding at easier versions of a problem (skidding on wet ground) helped us reach success on the standard version (skidding on dry ground). This is a lesson we’ve been taught repeatedly, in differing contexts: mathematics1, bicycling, violin-playing, programming, etc. We often progress rapidly when we give ourselves easy, intermediate versions of our main tasks, to succeed on.

The challenge

One area this truth applies is in our personal problem solving efforts. Young Tim, I’m particularly grateful for your motivated stance towards maintaining a handle on the problems we’re facing. This includes your attempts to follow the suggestion from December’s post: making a list of all our problems. By now, you’ve realized that this task is a large one. In fact, the task is so large it is an obstacle. Here, our earlier lesson can offer some help.

First, I hope you take comfort in how expected it is that you are anxious to stop using anxiety to keep track of all our problems. You have operated in a stressful state beyond your capacity for decades. I would be suspicious if you were NOT anxious to exit this state of being.

My intent in this note is to help us with listing, with getting all our problems out of our mind so we can more easily prioritize and stay aware of them. Following our lesson on solving easier versions of a given problem, I suggest an approach which, although less direct, may be more successful than sitting down to write a single, unstructured list. As it is sometimes said, see transportation joke, sometimes the shortest path is the longer route that’s less traveled.

Here is the problem with December’s advice of listing our problems:

we feel overwhelmed because there are way too many problems.

Too many to list in one sitting.

Too many to hold in our mind at once.

Too many to review at once.

If we reframe our listing problem, one challenge we’re facing is how to stay aware of a large number of individual problems, without triggering feelings of overwhelm. Fundamentally, this is a challenge of organizing our issues.

The application

So, if listing our individual problems is hard,

what related items can we list more easily?

How can these easier lists help us complete the problem list?

How can we create intermediate packets?

Two easier and useful lists to create are:

- a list of our needs, at an abstract level

- a list of the practical areas in our life, that we use to meet our needs

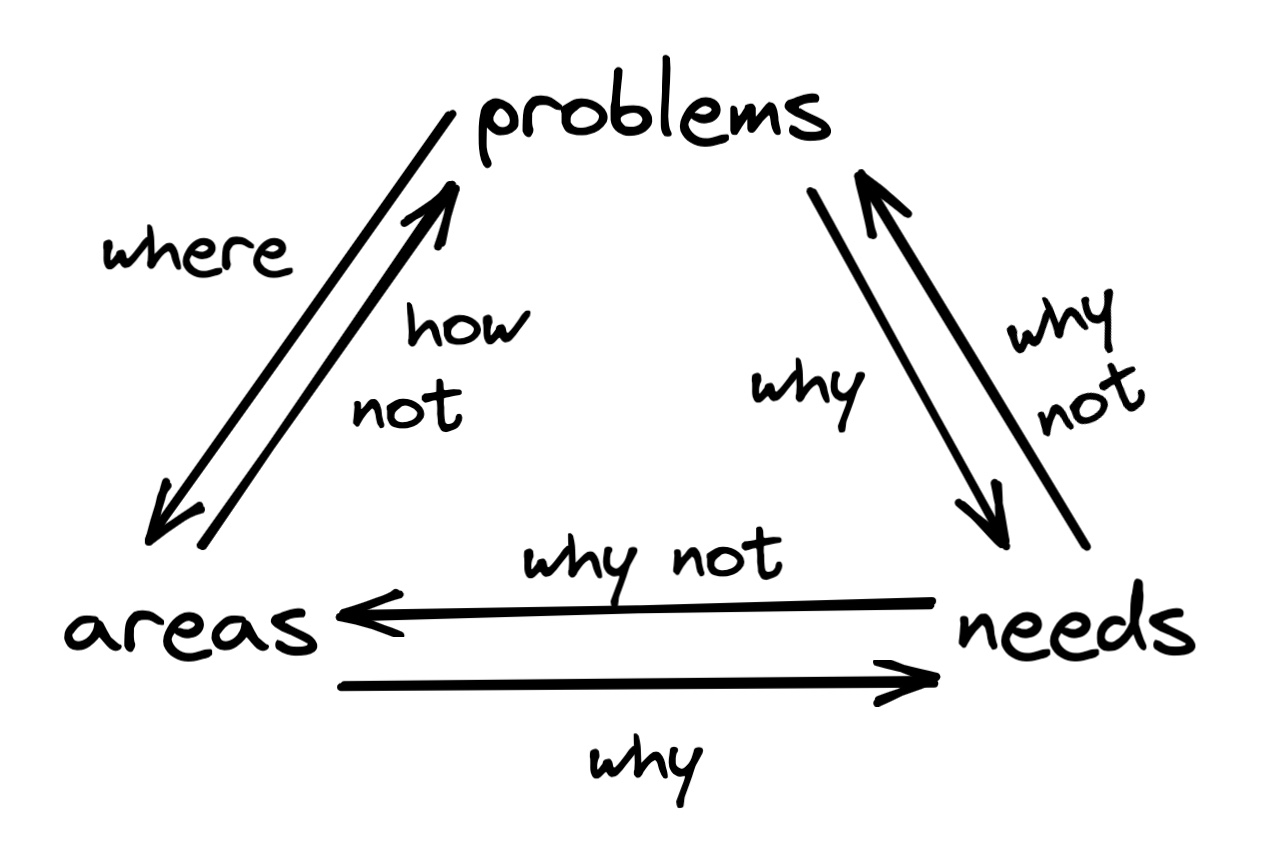

The diagram below depicts (i) these complementary lists,

(ii) our desired problem list,

and (iii) relations between them.

On the edges are questions that lead from one list to another.

For instance, problems indicate examples of

how not to manage related areas of one’s life.

Similarly, if we ask why are our needs not met,

we could trace most answers

to one or more problems in one or more of our life’s areas.

And so on, so forth, going around the diagram.

Here’s what I believe makes this triangular view beneficial. By projecting from the high dimensional list of problems, to complementary, lower dimensional lists, we can aid our review and planning for problem-solving. For example, I estimate that I have more than 200 problems. However, I list only 12 - 30 needs, depending on how I count. Likewise, when I list the various areas of my life, I have approximately 30. Such magnitudes are much less foreboding, and they are of the same order as “reasonably short” lengths of time– like a month.

Additionally, one can think of problems as undesired outcomes, with respect to our hill-climbing or improvement efforts against the following objective: maximizing satisfaction of our needs, subject to avoiding system failure in any one of our life’s areas. Listing our areas and needs, and connecting them to our problems, helps us stay aware of the underlying components giving our problems relevance.

So how can we reap these benefits? Start by listing the areas in one’s life: reviewing, planning, bicycles, nutrition, health, etc. Then, list the fundamental needs you have in life. Finally, think of the problems you are currently facing. List all that come to mind before you feel intimidated by the number of issues. When you’re done with your initial listing, you can categorize your initial problems into their respective life areas and associate the problems with the (unmet) needs that they relate to. Now, we’ll be able to use the areas and needs as categories, to cue our review and to sequentially list problems in.

Young Tim, I hope this advice helps you create an overall view of our problems.

I’m excited to see where we’ll go once we have a fuller view of the terrain!

Till next time:

may the storms smooth your path,

and where an even younger us may have feared loss of control,

may we find joy in life’s most wicked spins.

Take them and make them easy!

-

See, for instance, George Polya–author of the mathematics classic “How to Solve It.” Polya suggests, as one strategy to deal with hard problems, to solve easier but related problems. ↩