Digest before you express

Efficiently sequencing organization, internalization, and expression

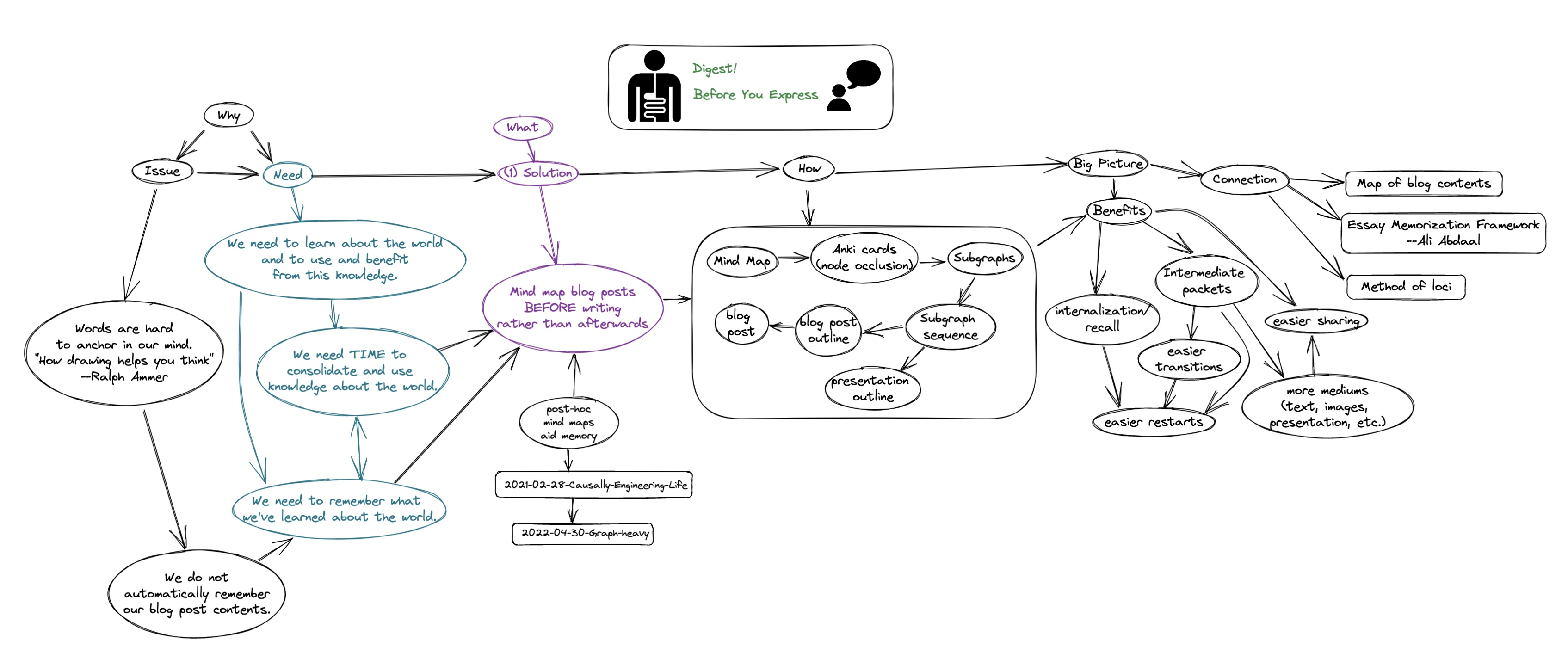

Digest before you express

The challenge

Dear Young Tim,

Do you recall the balmy July afternoons of our earliest youth? When we shared summer vacations from school with our sisters? We played on the sidewalk: my sisters blew bubbles, and I ran them down. I was determined to grasp each one before it hit the pavement. Though the chase was great fun and the colorful orbs beautiful, we never could hold onto those slippery bubbles. Bubbles are ephemeral, and as it turns out, words are similar. Or as put by Ralph Ammer,

One problem with written words, for instance, is you have to go through them line by line, word by word to know what they say. And as soon as you have, those words quickly disappear and vanish into a grey texture again. It is hard for us to anchor words in our minds, […]. — How Drawing Helps You Think

Unfortunately, it is not just the words of others that are hard to hold onto. The aforementioned slipperiness also films words drawn from the wellspring of our own mind. For example, over time, we forget the contents of our own blog posts.

This forgetting is problematic, because we must remember our blog posts to maximally benefit from them. As noted in Sadhguru’s article 1 on organizing one’s mind and body for success, “[i]f you suffer your failure it is bad enough, but if you suffer your success, then your life is 100% tragedy.” To succeed in writing to ourselves, and to then struggle to remember these writings is indeed a tragedy.

Needs

So Young Tim, what is it that we need to avoid tragedy, or put more constructively, what do we need to flourish? We already noted that we need to remember the content of our blog posts to most benefit from them. Relatedly, if we consider life more broadly, then as noted by social worker Peter Gerlach, we need to “learn about the world, and to use this knowledge” (implying remembrance of our learnings). Hidden in this general requirement is a complementary need for time. Specifically, we need time to consolidate, ingrain, and use our learnings about the world.

In practice, there is tension between our needs for time and for remembering. Memory improvement efforts require an (at least initial) investment of time, and these efforts feel like “extra work” when performed after information consumption. Indeed, we’ve repeatedly chosen time to create or consolidate learnings over time to ingrain them. That is, despite our desire to remember our blog posts, we’ve only covered a few of them using memory encoding techniques. How can we understand our eschewal of post-consumption, memory-aiding study efforts, and how can we act effectively to meet our needs given our newfound understanding?

Solutions

Internal Family Systems (IFS) offers one approach for getting to know parts of ourselves that may favor particular decisions or hold particular feelings. Integral to the IFS process is developing a sense of compassion towards our parts of mind. This compassion often comes from recognizing our parts’ positive intentions. Regarding our decisions to avoid memorizing past blog post contents, our positive, underlying desire was to be time and energy efficient. We don’t like activities that feel like extra work.

Focusing on this goal of efficiency, i.e. taking the perspective of the study-avoidant part of ourselves, we see redundant efforts in our current process for consolidating our learnings using our blog. Currently, we first organize our thoughts on what we’ve learned about the world, and then we write our blog post. In practice, we next wait some time until the post is no longer top of mind, then we extract the post’s organization and details. Finally, we create and memorize a mindmap based on this structure and fine points.

Our current procedure is based upon prior, valid realizations. For example, we’ve previously posted about how post-hoc mind maps help promote understanding, organization, and memorization. We first noted this phenomenon in Causally Engineering Life, and we discussed it more thoroughly in Heavy on the Graphs. Still though, our procrastination in using this process points to additional physical and mental realizations. In this case, our feelings and sensations suggest that we can make better choices.

in hindsight, of course, making better choices is difficult. Luckily, life often gives us the chance to make better decisions going forward. In particular, we believe some variant of the process above to be amongst the most beneficial way to internalize already written posts. However, when considering posts yet to be written, we can indeed streamline our process for remembering what we’ve learned. To do so, we use a software engineering principle for promoting efficient programming: “Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY).” The idea is to be efficient by avoiding duplication. By inverting our process so we create and internalize mind maps before writing our blog posts rather than afterwards, we can move from two instances of mental organization to one.

Mechanisms

Why…Why does this inversion benefit us? Our idea is founded on the experience that writing a blog post is analogous— in terms of information organization— to drawing and memorizing a mind map, yet we generally find it easier to describe what we see than to see what has been described to us.

Mind maps are images that are “seen”

whereas blog posts are descriptions that are “read.”

Accordingly, in a more mathematical notation,

we might say

blog_post[mind_map(thought)] = “reading from mind-map” = “explanation”,

mind_map[blog_post(thought)] = “drawing from blog post” = “organization”,

and blog_post[mind_map(thought)] < mind_map[blog_post(thought)] in difficulty.

We hypothesize that this asymmetry in ease of composition comes from talking (and titling as a special form of talking). Talking provides the detailed information and titling of mind map sections (i.e. subgraphs) provides the sectional information that is present in a blog post but missing in a mind map. Conversely, we know of no similar intermediary that provides the relational / structural / spatial information that is present in a mind map but missing in a blog post. As a result, we can make a mind map, and then produce a blog post “cheaply” by talking through and talking about our mind map. The process is a translation of one’s existing mental organization.

In comparison, writing a blog post only negligibly lowers the effort required to draw the mind map of that posts’ ideas. Much mental effort is still needed to choose and clarify connections between nodes in the mind map or the lack thereof. Writing before drawing, essentially requires two mental organizing efforts.

Process description

So, just how are we using mind maps while writing our blogs?

To capitalize on and operationalize the translational ease described above, we’ve found the following process useful so far.

First, to document, clarify, and organize an idea, we start by making a mind map, either on paper or digitally. Next, we create anki questions based on this mind map. These questions take the form of node occlusion cards, where each question covers (i.e. occludes) one node. The answers are whatever was originally contained in that node. After making one node occlusion card per node in the mind map, we then turn to create subgraphs. These subgraphs are used to create more node occlusion cards— cards that now cover all nodes of the subgraph at once. Note that our subgraphs are based on intuitive groupings of nodes, thereby assisting with chunking and ultimately retention.

After splitting the mind map into subgraphs, we then order these subgraphs in an intuitive sequence. We act as if we were using the subgraphs to explain (er, present) the entire mind map to someone else. Like chunking, this sequencing with aim to explain also helps our memory efforts. Continuing the explanation exercise, we note the questions that we would ask, such that the subgraph was the answer or a visualization of our answer.

If desired, we can use the questions and their associated subgraphs for a presentation outline. We could use the questions as slide titles, and we could use the subgraphs as the body of the slides. Next, we use the earlier sequence of subgraphs to order both the slides and questions. The ordered questions directly form our blog post outline. Lastly, we create the post by answering the questions, describing the subgraphs, and elaborating on the subgraphs.

The forest behind the tree

Okay, so what does all of this get us in the end? If describing our motivation and process is like drawing the roots, trunk, and leaves of a great tree, then this is a fine time to step back, to appreciate the fruits of our labor, and to take stock of the connections2 we’ve forged with other trees in the forest. Metaphors aside, let’s consider the bigger picture in which our digestion before expression is situated. What is the spectrum of benefits from this practice, and how do we relate to ourselves and others through this process?

Benefits

We start by looking at what we gain from this procedure. Our first obvious benefit is greater internalization and recall of our blog posts, relative to not using any memory techniques to study the posts. The next set of benefits stems from our creation of multiple intermediate packets:

- mind map

- set of anki flashcards

- set of subraphs

- sequence of subgraphs

- presentation (outline)

- blog post (outline)

These intermediate packets fill out rungs on a ladder. These rungs enable smoother transitions between initial thought and completed statement. That is, between initial thought and blog post and / or presentation. Moreover, the easier transitions combine with our greater recall of our main points. With both, we become more confident in finishing meaningful units of work per session. Finally, this increased certainty reduces our reservations to restarting after breaks or distractions.

Not only do we (re-)start more easily, we also end in grand fashion as well. By creating these intermediate packets, we greatly diversify the mediums in which we express our thoughts. For example, we create images (mind maps, subgraphs, slide decks), text (blog posts), and potentially audio or video, if we record our presentations. These diverse media ease our sharing our thoughts with other people, as some individuals will find some media more accessible than others.

Think of images as a medium versus text. In doing so, let’s recall the words of Ralph Ammer, quoted above. His quote actually ends by saying “[i]t is hard for us to anchor words in our minds, and drawings can help make them stick.” We can combat the aforementioned slipperiness of words, by leveraging the stickiness of images, images we create as intermediate packets during our digestion process.

Shifting our attention from images in general, to the specific image category of mind maps, we can consider the experience of author Elizabeth Chin in her autoethnography “My Life with Things.” She too “mind” mapped her writing—her book—before (fully) writing it. She states

As with many other writers, there came a time where I felt stuck. […] The problem was that I really could not see how to shape what I had written into a book. My friend Susan Ruffins rescued me from that state. She took the manuscript in hand, laid out entries across her office, [i.e. made a physical map of documents,] picked them up in one spot and put them down in another […]. In my case I needed a guide through the thicket. —p. 32

This is the role played by mind maps. They provide a pictoral guide through the thicket of words in our posts, for ourselves and for others.

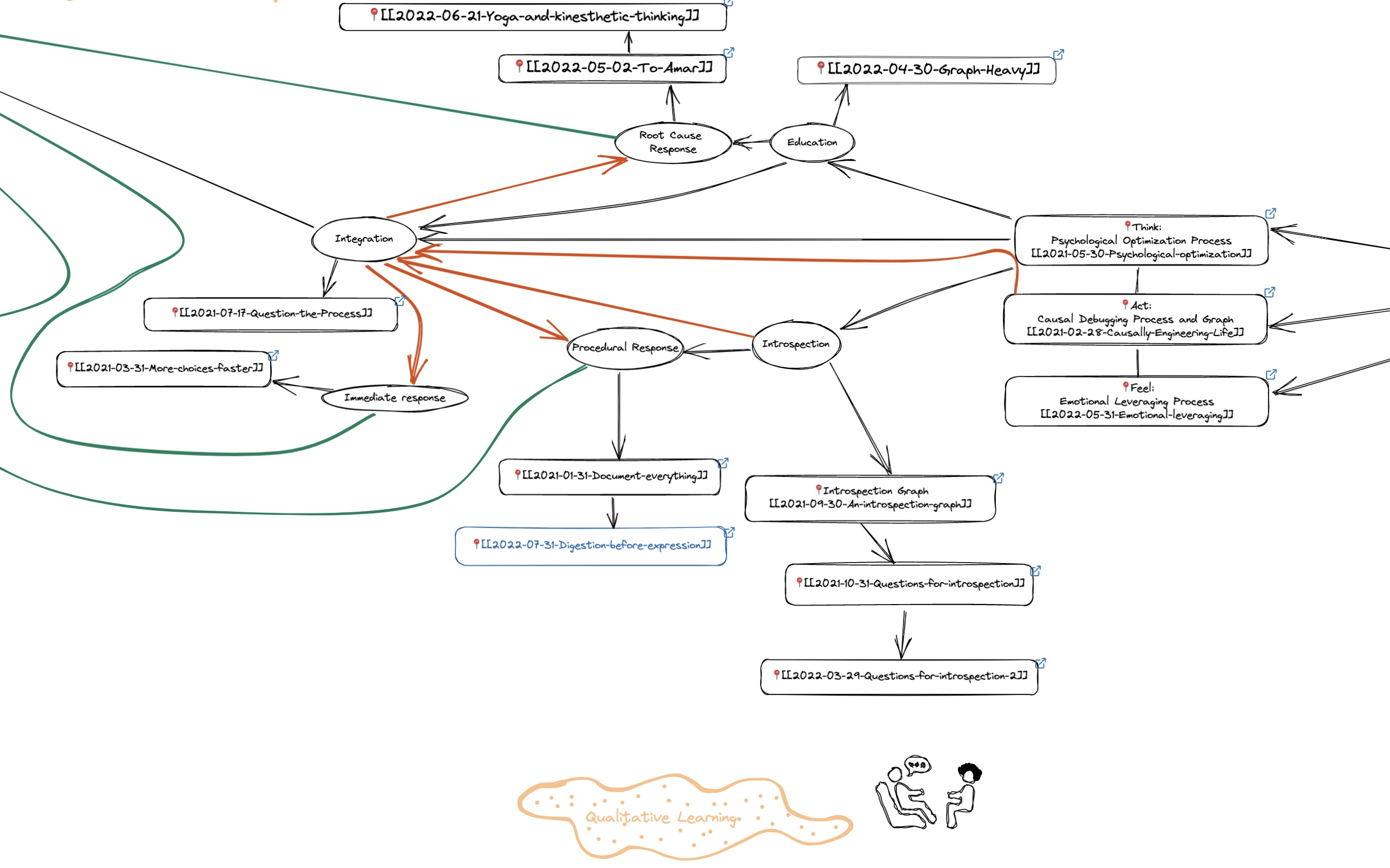

Connections

In much the way that mind maps make clear the connections between nodes, lets clarify some of the many connections forged by our practice of digestion before expression. In particular, we can consider how this practice connects us to ourselves— to our previous thoughts and to our blog posts. Below, we show an updated view of our blog’s map of contents. Specifically, it’s a view of the qualitative learning subgraph, where many of the recent blog posts are located.

Though this post discusses mind maps, as does Graph Heavy, we are describing a procedural change in how we write our blog posts. As such, we see this post as a descendant of Document everything, giving us one example of algorithm change, development, and documentation. In this case, our procedure tells us how to chronicle our monthly learnings for our younger selves.

If we continue broadening our horizons, we can observe how digestion before expression connects us to our contemporaries. For instance, consider fellow Building a Second Brain alumnus Ali Abdaal. In his 3rd year of medical school at Cambridge University, he won the top exam results prize. To do so, he made about 50 essay plans in the form of mind maps, and he used anki flashcards to memorize them. At an abstract level, our processes are analogous: mind map -> anki -> document outline. As Ali’s results and our own experience show, this process performs well in both academic and in personal settings!

Finally, we can look at the connection to others throughout history. For instance, take the map in mind map. We commit these maps to memory, internalizing the text, images, relational information (arrows and meaning), and spatial information about what is where. The memorization of such spatial information is precisely the Method of Loci.

This method is an ancient memory technique that has been used by orators to deliver long speeches (i.e. expressions of thought). In the Method of Loci, one takes pieces of information to be remembered and one places each piece of information in relation to each other. This placement can be on an entirely fictional map, as when mind mapping on a blank page. Alternatively, the placement may be on maps inspired by reality, such as on maps of indoor or outdoor locations. Finally, one memorizes the set of loci (points, locations, nodes, etc.), and one memorizes a path or journey through these points, recalling the information along the way. Much the way our mental digestion takes place before expression of our blog posts, the Method of Loci was used before a speech was given.

Here, we see our practices comfortably situated amongst a long historical line of individuals who sought to remember what they’ve learned and who sought to remember what they wished to share. In our youngest days, when we first learned of those slippery bubbles, we tried to grab hold of them, but we could never share them that way. All along it seems, as with many words, a picture would have better captured the beauty and significance of the moment, both for our memories and for others. Going forward Young Tim, when recalling and expressing a word from the wise, we’ll be greatly looking forward to your big pictures: internalized, refined, and vividly held for the rest of us to see.

-

We noted this article due to its motivation of yoga as effective, kinesthetic thinking ↩

-

The notion of connection is not hyperbole. Trees communicate and are connected. ↩