Yoga and Kinesthetic Thinking

Valuing yoga and the use of movement as a way of thought

Yoga and kinesthetic thinking

Daaaaaaamn, you TIGHT!

So went the familiar refrain across New York City schoolyards throughout the 2000s.

Issues

Dear Young Tim,

Like the best slang sung by urban youth, the truth of this phrase resonates at multiple levels. Contextually, such proclamations often came publicly, after blatant disrespect, such that recipients of the disrespect were now emotionally taut— i.e., close to emotionally snapping. Physically, bodies often mirrored states of mind. Tension would be etched in tight lines across our forehead, in pursed lips, or in our tightly drawn eyelids.

A therapist once told us that people of color frequently somatize their stress. That is, people of color frequently channel and express their stress as varied physical ailments and as potentially painful sensations. Such findings have been reported as far back as the 1990s, by way of the U.S. Surgeon General (2001, p.60). Far from an impersonal statistic, we embody these findings daily, as we regularly and intensely somatize our stress.

One problem with somatization is that the chronic, unmitigated stress that is being physically channeled, harms the mind and body. An incomplete list of mechanisms of harm includes

- hypertension (high blood pressure)

- postural and musculoskeletal problems

- early onset and increased rate of hair loss

- mental trauma

- and more.

To be clear, it is not that chronic stress is harmful by itself. For example, think of professional athletes. They place themselves under chronic physical stress, yet they are often in great health, at least by a handful of measures. What seems crucial to their ability to benefit from chronic stress? In a word: rest.

Needs

Our unmet need for rest points to a related and complementary, unmet need for peace. Of course, life is ever changing, so we will hardly be at peace all the time. Accordingly, we need stress mitigation methods— to restore our sense of peace after we have been (di)stressed.

In particular, we need both physical and mental stress mitigation methods. Given the intensity and frequency of our somatization, we need counterbalancing, physical methods to calm our body and thereby calm our mind. For further balance, we also benefit from mental practices, where we use our mind to calm our bodies (e.g. meditation). These mental practices are of particular help alongside and, if necessary, as substitutes for our physical stress mitigation methods.

Yoga

One solution that meets both our needs for physical and mental stress mitigation is Yoga. According to Wikipedia, one of the central aims of yoga is to “yoke” or harness one’s body and mind together, to attain liberation from suffering (presumably both physical and mental). That certainly fits our definition of stress mitigation!

There are a great many types of yoga, i.e. many ways of performing this yoking. In the United States, yoga is most associated with yoga poses or postures. However, in older practices such as Ashtanga yoga there are eight parts of yoga, and only one of them is the postures. For the sake of our discussion today, we’ll mostly focus on yoga as comprising at least two parts: breathing and postures.

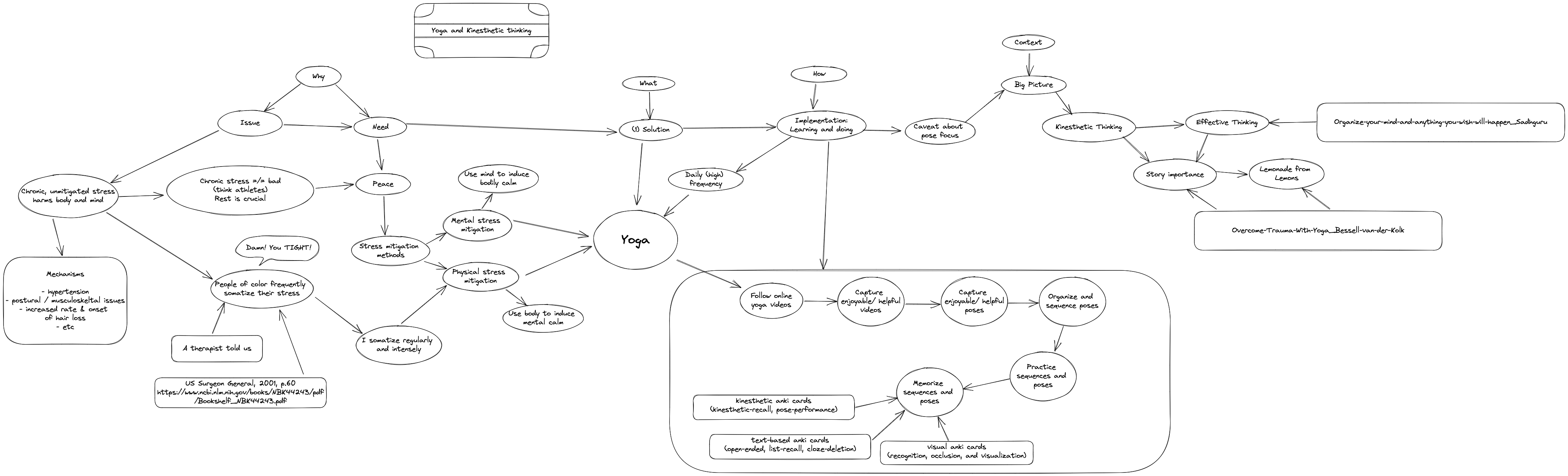

Learning and doing

So, how can we learn and practice yoga? How can we make use of this stress mitigation tool?

Like any of our other interests, the first thing we can do is engage with the topic regularly. In our case, daily or with as high a frequency as we can manage. We are stressed, even if only in small ways, on a daily basis, so we may also want to mitigate physical expressions of our stress— daily, when possible.

Specifically, we have followed the following process. First, with no pressure, we followed along with online yoga videos that looked interesting. Next, we noted and stored videos that we found useful or enjoyable. We then took screenshots of poses that we found useful for relieving tension or simply enjoyable in physical sensation. We did the same with descriptions of breathing patterns. Once we had a small collection of poses (e.g. twelve poses), we began organizing them into physically intuitive sequences. We then created names, images, and narratives for those sequences, and we began practicing these sequences daily. Finally, we committed these patterns, poses, and sequences to memory using anki flashcards. These cards are of many varieties, including

- visual anki cards featuring pose recognition, node occlusion in diagrams, and visualization of poses,

- text based anki cards featuring open-ended responses, list recall of pose names, and cloze deletion of pose-names in sequences, and

- kinesthetic anki cards featuring “kinesthetic recall” (i.e. recall of how poses felt physically) and flashcards calling for performance of breathing patterns, poses or pose sequences.

All together, these practices multiply encode yoga knowledge as we accumulate it, and they present multiple ways of learning and “doing” yoga.

Big picture

Given the preceding focus on poses and breathing patterns, caveats are in order here. Yoga, and our practice of it, is about far more than memorization of specific postures and ways to stay alive (i.e. breathe) while holding them. There are multiple levels of further significance to consider. As mentioned earlier, there are the “Eight Limbs” of Yoga. We can broaden our view even further though. We can consider yoga and our practice of it as an example of “kinesthetic thinking,” and finally, we can consider these both within our map of blog contents and in relation to relevant, existing posts.

Kinesthetic thinking

First, what do we mean by kinesthetic thinking. On one hand, we have prior definitions of thinking as internal communication between parts of ourselves. Here then we might imagine kinesthetic thinking is internal communication between parts of ourselves for the purposes of or while making movement.

On the other hand, we can reason by analogy. Author and graphic facilitator Brandy Agerbeck has defined visual thinking as “making a drawing to make meaning for ourselves” (video). Accordingly, we might then think of kinesthetic thinking as making movement to make meaning for ourselves.

Putting these two thoughts together, we define kinesthetic thinking as internal communication between parts of ourselves in order to, or while, making meaning by making movement. Here, yoga is an immediate example of kinesthetic thinking. During yoga, messages are communicated between various parts of our body and our brain, and these messages help us make meaning of how we have been affected by physical and emotional events in our lives. Additionally, our brain and body exchange many messages in order to put ourselves into the various poses. Perhaps most creatively, when using anki cards to cue mental recall of how the poses felt, we are literally thinking kinesthetically. This same is true when we use flashcards to cue performance of specific postures.

Effective thinking

Continuing along these lines, we can identify kinesthetic thinking as one mode of effective thinking. When thinking effectively, our internal communication consciously aims to meet our needs. Indeed, in as much as being aware of and caring for our (physical) state is a need, and as much as maintaining minimum levels of peace in our body and mind is a need, yoga is about internal (brain-body) communication to make movement in order to meet our peace and awareness needs. More fundamentally, yoga is about learning to “yoke” or harness the mind and body together. The idea is that once harnessed, we can most effectively direct our mind and body towards meeting our needs.

As wishfully put by yoga instructor Sadhguru,

If you bring your mind to a certain level of organization, it in turn organizes the other three dimensions of your system— your body, emotion, and energies. Once these four dimensions are organized in one direction and kept unwavering for a certain period, anything you wish will happen.

Though likely false in absolute terms, the general principle of harnessing both mind and body for effective thinking and action is clear.

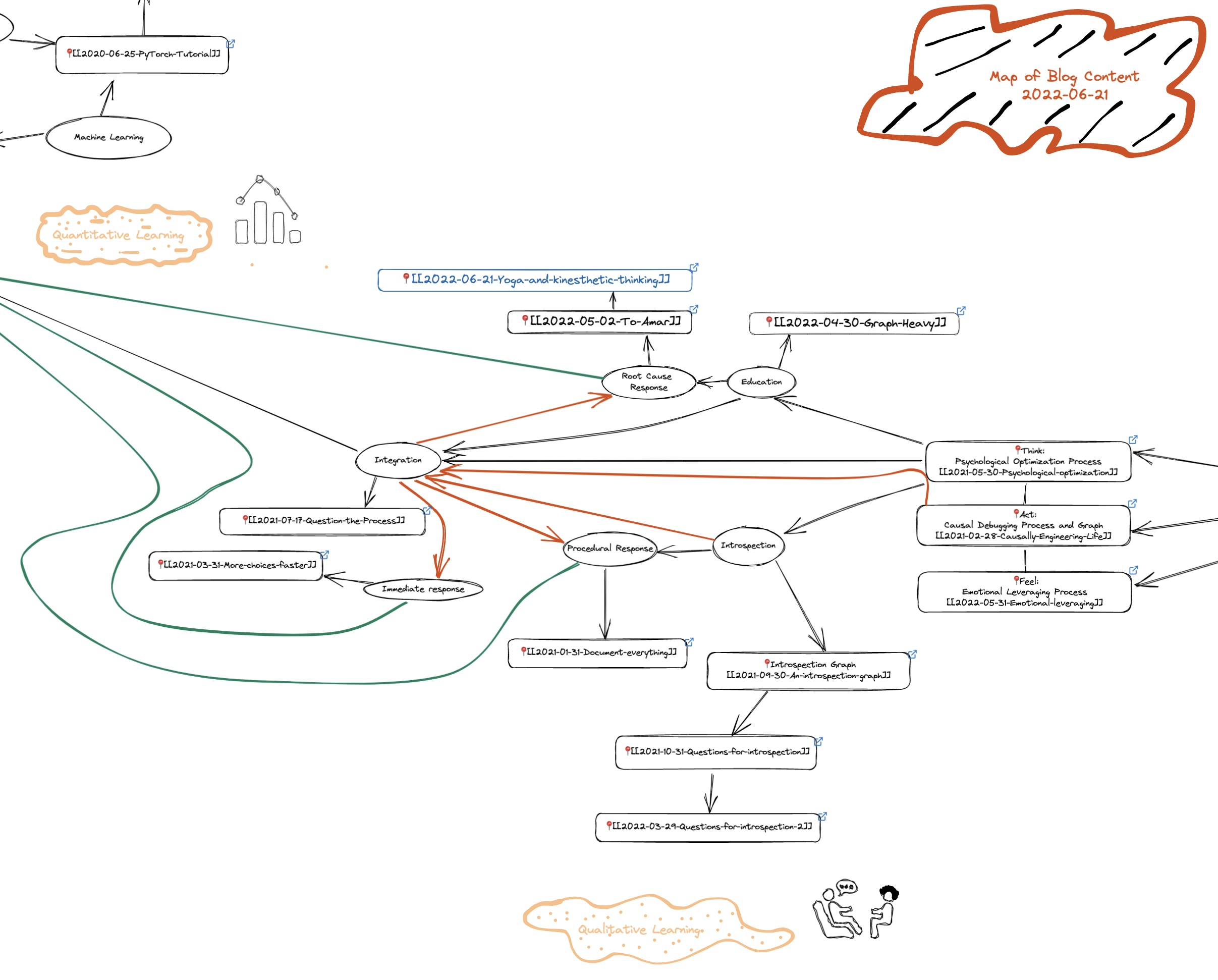

Map of blog contents

Zooming out, we can place the topic of yoga and kinesthetic thinking within the broader context of our blog’s thoughts. Increasing the importance we ascribe to yoga and kinesthetic thinking is a core change in our values and valuation of these activities. In other words, this is a root cause change, as pictured below.

Growth as a stretch

Finally, we can consider links between yoga and our earlier posts, such as those on problem understanding and on changing our life’s stories in the wake of trauma.

As we noted before, the central challenge facing a traumatized individual is to change their stories about how the world works. Recall that a real threat after trauma is becoming trapped with a worldview that is predictively incorrect and repeatedly results in the individual experiencing harmful events. These incorrect stories are trapped in the sensations our bodies produce as well as in our minds. Psychologist Bessel van der Kolk (author of “The Body Keeps the Score”), points out that trauma

is about how your body gets stuck in being frozen or in heartache and gut-wrenching feelings. […] Emotions are about physical sensations. […] Trauma is about having unbearable physical sensations.

While psychotherapies help us move past our harmful thought patterns, yoga helps us move past the physical tensions and pains associated with those thoughts and their related events. Yoga does this in at least two ways.

One obvious way is by giving us an arena where we can successfully face and then overcome initially unpleasant physical experiences. Recall when we were troubled by some day’s events, and we slept poorly, hurting our neck as a result. We could come to the yoga mat, do some stretching, and in a little while, walk away feeling better. As van der Kolk states,

When you’re a traumatized person, it feels like nothing will ever change. When you do yoga, you notice you can put yourself in some damn uncomfortable pose; and before too long, it’s gonna be over. And you get that sense of time, which is a very important thing in helping to overcome trauma because sucky things happen to people all the time. And the way you move through life, you say, okay, today it sucks; but tomorrow is another day. So you have this sense of time that allows you to have that perspective. When you get traumatized the perspective of this, too, shall pass disappears. And so reestablishing that sense of time, which yoga does so well, is now a very important part of what yoga can do for people.

A second way that yoga helps overcome unpleasant sensations is by raising our awareness of these feelings, as paradoxical as that may sound. Many times now, we’ve come to do some familiar pose and found ourselves with an unfamiliar tightness that we were not already aware of. Had it not been for attempting the various postures, we may have simply gone on compensating for the tightness without any conscious awareness of it. Through yoga, we often become aware of areas of tension in our body, and we are able to literally stretch past these points of initial resistance. In this way, yoga helps us to change both physically and metaphorically— by recognizing our limitations and by then carefully moving beyond them.

This effort parallels the drafting of problem statements required to make lemonade from lemons. In both cases, changing our unpleasant feelings requires awareness. Thankfully, to quote van der Kolk once more,

Yoga really helps people to really contain themselves and to safely experience their bodies. So that is really much of my attraction to yoga is understanding that when you get traumatized you don’t really want to feel what you feel and know what you know. And that really is part of at the core of the problem. […] It [yoga] makes it possible for people to feel things that they may be very afraid to feel.

So, knowing now what I know, I wish I told you long ago how beneficial practicing yoga would be. I wish I would have told you how much it would help you stretch beyond your perceived limits. As the saying goes, although never late is better, it’s still better late than never. Until my next note, Young Tim, may you find peace in many poses!

P.S.: Happy International Day of Yoga! 🧘🏾♂️