Growing pains

Practices for accepting and building from awareness of undesired truths

Growing pains

99 problems

Dear Young Tim, sorry for this delayed message.

There are times when we will conclude we are facing “tons of problems” and that there is much about our life that we dislike. In this particular brand of displeasure, we will have plenty of company.

For instance, author and motivational speaker Tony Robbins once noted that

[t]here is a gap between who you are, what you want, and where you want to be. There’s a massive gap. Awareness and the acceptance of that awareness is the bridge to the future.

While awareness and acceptance of these gaps may be our bridges to our best futures, we still have to cross them. And like trying to cross a rickety, wooden suspension bridge with missing planks: the experience can evoke numerous unpleasant feelings and undesired behaviors (freezing, panicking, retreating, etc.). These unpleasant feelings are growing pains, and they are absolutely to be expected.

Needs

From the perspective of internal family systems (IFS), we have parts of mind that are activated when we sense that our needs and desires are unmet, i.e. when we become aware of the gaps between who we are, what we want, and where we want to be. When activated, these parts of mind generate unpleasant sensations, and they motivate coping behaviors meant to “make us feel better” or to “keep us safe”, regardless of the net effects. For example, we are quite talented at devouring large quantities of sweet foods when stressed, at siphoning away our time by escaping into books/shows/fictional-worlds, and at otherwise ignoring issues, until we believe we can deal with them.

Instead of employing such dissociative techniques, we need self-regulatory methods that re-establish mental and emotional “okay-ness” while accepting awareness of our present reality AND while preventing or minimizing detrimental second-order effects of our actions. In IFS terms, we need ways of re-establishing a sense of “Self”, wherein we feel:

calmness, clarity, curiosity, creativity, courage, confidence, connection, compassion,

perspective, presence, patience, playfulness, and persistence.

Today, we’ll focus on a subset of these qualities, and on related methods we’ve found useful for bringing them about.

Reminders of Gendlin’s Litany

Let’s start with calmness and clarity. We cannot have clarity about something, if we cannot see and sense that thing closely. However, establishing calmness often starts by distancing ourselves from painful experiences. Do we not immediately pull away from painfully hot items to prevent burns? Do we not immediately look away from the sun to prevent eye damage? How then can we pursue both calmness and clarity with regard to our growing pains?

One line of thinking is given in Causally Engineering Life and in Emotional Leveraging. If our immediate response involves seeking calmness by ‘opposite to emotion actions,’ by distancing, or by otherwise dissociating ourselves from painful realizations of our life’s problems, then our procedural and root cause responses remain opportunities for building and for building from clarity. To effectively respond to our problems by changing what we do and how we are, we benefit from looking at and studying our problems. Here, staying calm allows long-enough engagement with our problems so we can usefully learn about them and how we contribute to them.

Regularly reviewing affirmations has helped us more calmly observe the problems in our life’s systems. For example, it is especially helpful to remember the Litany of Gendlin: that

[w]hat is true is already so.

Owning up to it doesn’t make it worse.

Not being open about it doesn’t make it go away.

And because it’s true, it is what is there to be interacted with.

Anything untrue isn’t there to be lived.

People can stand what is true, for they are already enduring it.

—philosopher and psychologist Eugene Gendlin,

Focusing, ch 11 The Listening Manual

Though our initial reaction is to shrink away from the sight of our broken life systems, much like we’d shrink away from the sight of broken bones, looking at our problems does not intrinsically make them worse. Further, ignoring the problem doesn’t make it disappear. And finally, we already endure the negative consequences of our broken systems, even if we don’t look at the dysfunctions directly. In fact, looking at what’s broken is the first step to fixing it.

Remembering that we are already impacted, that observing doesn’t make our problems worse, and that we need to look at our problems to resolve them helps us remain calm while surveying our wreckages. Procedurally, cloze-deletion anki-flashcards promote our remembering of Gendlin’s Litany. Anki’s spaced repetition helps keep this knowledge generally accessible. And by tagging this and other affirmations, we further facilitate in-the-moment self-regulation with “custom study sessions,” whenever stress from life-system firefighting triggers our dissociating reflexes.

Life(style) acceptance tests

In addition to calmly gaining a closer understanding of what is wrong, a complementary practice is to reconnect with perspectives that are generally useful for our specific problems. Such perspectives promote hope and reassurance by providing us with ideas and by connecting us with thoughts and stories of others who successfully resolved similar problems. For example, author and successful media personality Tom Bodett asks

[t]he difference between school and life?

In school, you’re taught a lesson and then given a test.

In life, you’re given a test that teaches you a lesson.

Bodett’s observation recalls the software engineering perspective and practices of Test Driven Development. Within this paradigm, we start with all our systems’ tests failing. These failing tests are problems, but the fact that we start from failure is intentional and helpful. By starting with failing tests, passing tests in the future serve as evidence that the system changes we make are causing the expected behaviors and outputs.

If we fell over, writhing in discomfort at each failing test, we would get nowhere—professionally or personally. Instead, as engineers building and maintaining the systems we desire, we routinely collect as many of these distinct tests as we can, from hypothesized or (often) observed user stories. We then use these tests of the accepted behaviors of our systems to guide and specify our life system designs.

Throughout this process, Bodett says that life’s tests teach us lessons. As in test driven development, we initially fail life’s tests. We believe that learning our tests’ lessons, starts by documenting the tests. That is, we must activate our curiosity, starting with clear statements of what outcomes and functionality we want from our life’s systems. As noted above, to be systematic in designing our systems so they function as desired, we document and store our system specifications. We do not store specifications only in our memory, just as engineers do not keep design regulations or software test suites only in their memory.

To write and document our acceptance tests, one option is to use the same basic template that we use to log our emotional problem-statements. That is, we can write something along the lines of

GIVEN {{these-circumstances}}

WHEN {{this-happens}}

THEN [I will face {{these-concerns}}]

and I will decide to DO {{these-acts}},

as opposed to {{these-other-acts}},

and I will decide to FEEL {{these-feelings}},

as opposed to {{these-other-feelings}},

in order to satisfy {{these-NEEDS}} to {{these-extents}},

while accepting {{these-downsides}}.

As before, elements in curly-braces, i.e. ‘{‘ and ‘}’, are to be replaced with our own descriptions. Clauses with rectangular-braces, i.e. ‘[’ and ‘]’, are considered optional and to be included at a communicator’s discretion. For future-proofing and accessibility, the tests can be stored in a plain-text format like markdown or ‘.txt’.

Our acceptance test template above captures the outcomes, behaviors, feelings, and satisfied needs that we want our life systems to generate. Together with our emotional problem statements, our lifestyle acceptance tests anchor our awareness-bridges to a better future. In particular, Tony Robbins points out that we need awareness of the gap between where we are and where we want to be. Our emotional problem statements document knowledge of where we are. Our lifestyle acceptance tests document knowledge of where we want to be. We then learn Bodett’s life lessons by:

- clarifying the gap or differences between our acceptance test and problem statement anchors,

- learning the reasons for these differences (through introspection and education),

- using our understanding to design new systems that bring about our desired realities

- and designing implementation processes for constructing these new systems in our life.

System diagrams

Lastly Young Tim, before running to learn our 4-part lessons from life’s tests, we can improve our chances of success by remembering to “look before we leap.”

As put by software engineer Robert C. Martin—one of the founders of Agile Software Development,

[b]efore you begin to code any software project,

you need to have some architectural vision in place.

TDD [test driven development] will not, and can not, provide this vision.

That is not TDD’s role.

Practically speaking, we benefit from diagramming our desired systems and their implementation processes, before we actually construct the systems and rely on them. These system diagrams offer stable connection to the architectural visions we hope to concretize; the diagrams provide a sharable artifact for critique and collaborative improvement; and the diagrams spark actionable ideas on where to focus our system building efforts. Even diagrams of our existing systems offer similar benefits, by helping us introspect and analyze why we are getting our current, problematic results.

Specifically, such diagrams focus on our system or process components and on how these components interact to produce our final and intermediate outcomes. This component focus leads naturally to questions of

- what components or process steps do not currently work,

- why not,

- and what would need to be true if the component or process step worked as desired?

With these answers in mind, we can identify as many major conceptual issues with our system as early as possible (i.e. before trying to perform each step or make each system component work), make informed time and cost estimates per component, and execute our plan for system construction— i.e., our plan for development that resolves our growing pains. Our diagrams thereby serve as the planks and ropes of the bridges to our future, steadying our crossing at each step along the way.

Conclusion

To summarize, we’ll surely encounter many problems in life. Becoming aware of these problems will be a painful experience. By remembering affirmations such as The Litany of Gendlin, we can help ourselves stay calm as we increase our clarity about our problems. Once we look at our current states, emotional problem statements serve as a decent way to document our problems. Taking the perspective of an engineer using tests to drive the design of our life’s systems, we’re next led to note the conditions and outcomes our system will provide when working acceptably. Finally, we can further borrow practices of system diagramming to document: our current system design, our desired system and its functioning, and a migration process for getting from our current to our desired system. Questioning and comparison of these diagrams support and jumpstart our efforts to clarify, build, and/or repair the components that together provide our desired system functioning.

Young Tim, may these practices, combined with our earlier thoughts, help us problem-solve “through the dash,” 🙏.

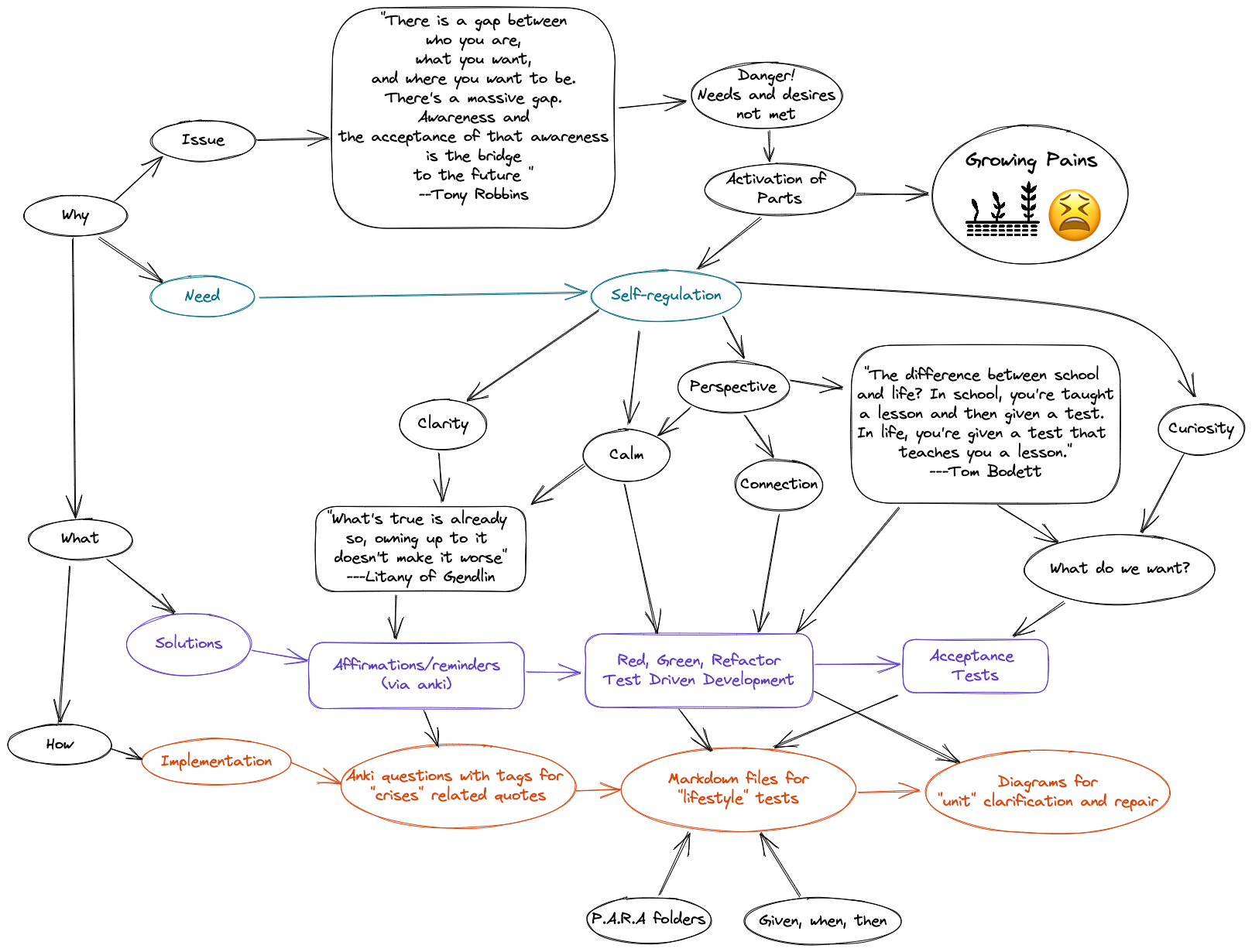

P.S.–To facilitate summarization and later recall, here is a mind map of this post.

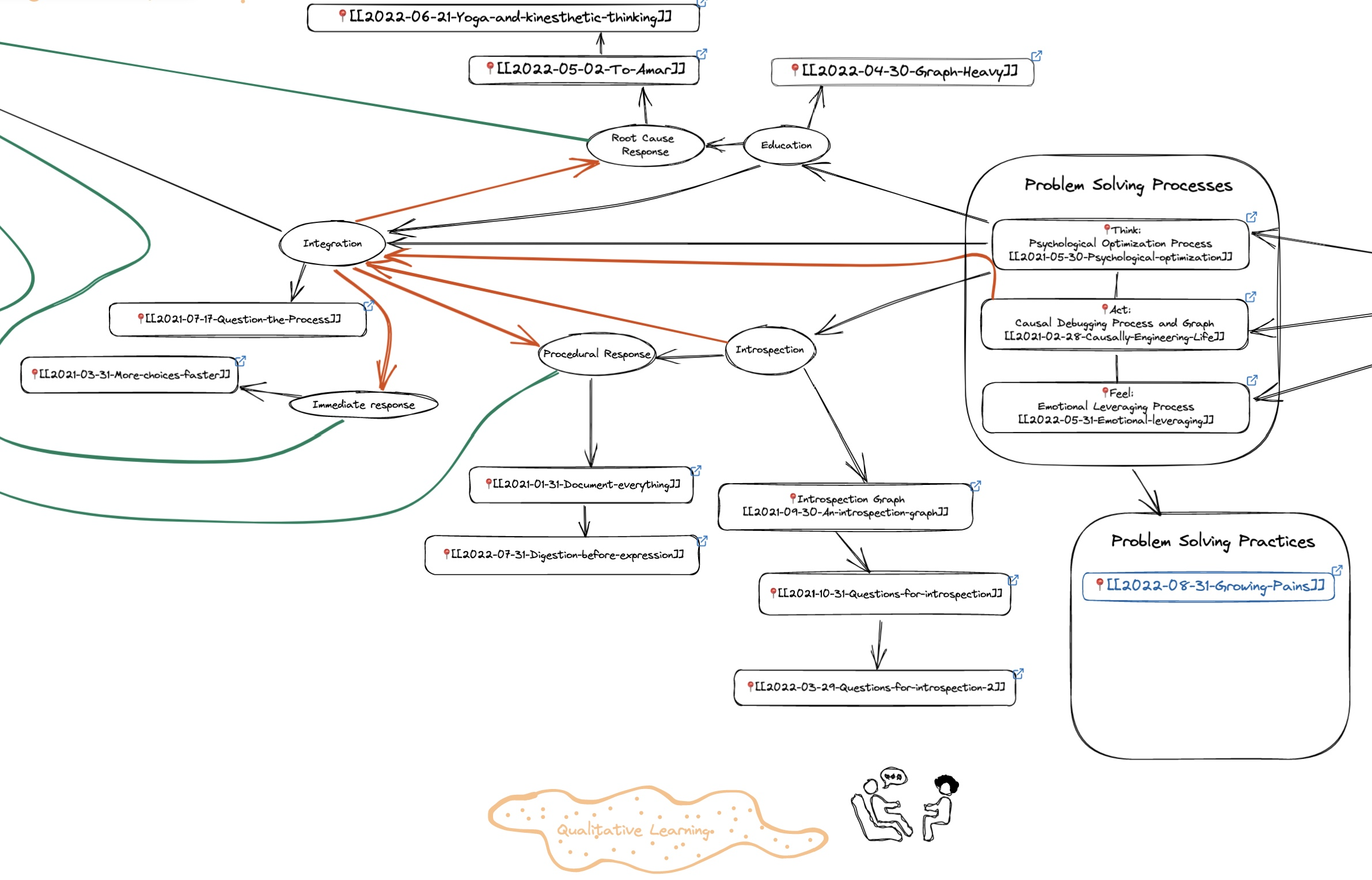

Additionally, to contextualize this message, here is as an updated map of all our blog’s posts. As usual, only the updated subgraph is displayed below.

Related Posts

-

Causally Engineering Life

Problem solving processes (action overview) -

Emotional Leveraging

Problem solving processes (emotional overview) -

On problems, areas, and needs.

Problem listing -

Heavy on the Graphs

Problem mapping -

Lemonade from lemons

Problem description -

An Introspection Graph

Problem analysis -

Questions for Introspection

Problem analysis -

Questions for Introspection Part 2

Problem analysis

.