Time Budgets

Benefits of budgeting 168 hours per week.

Time Budgets

TLDR

- To increase the probability of having an amazing week,

create an ideal budget that allocates 168 hours across our desired activities.

Overview

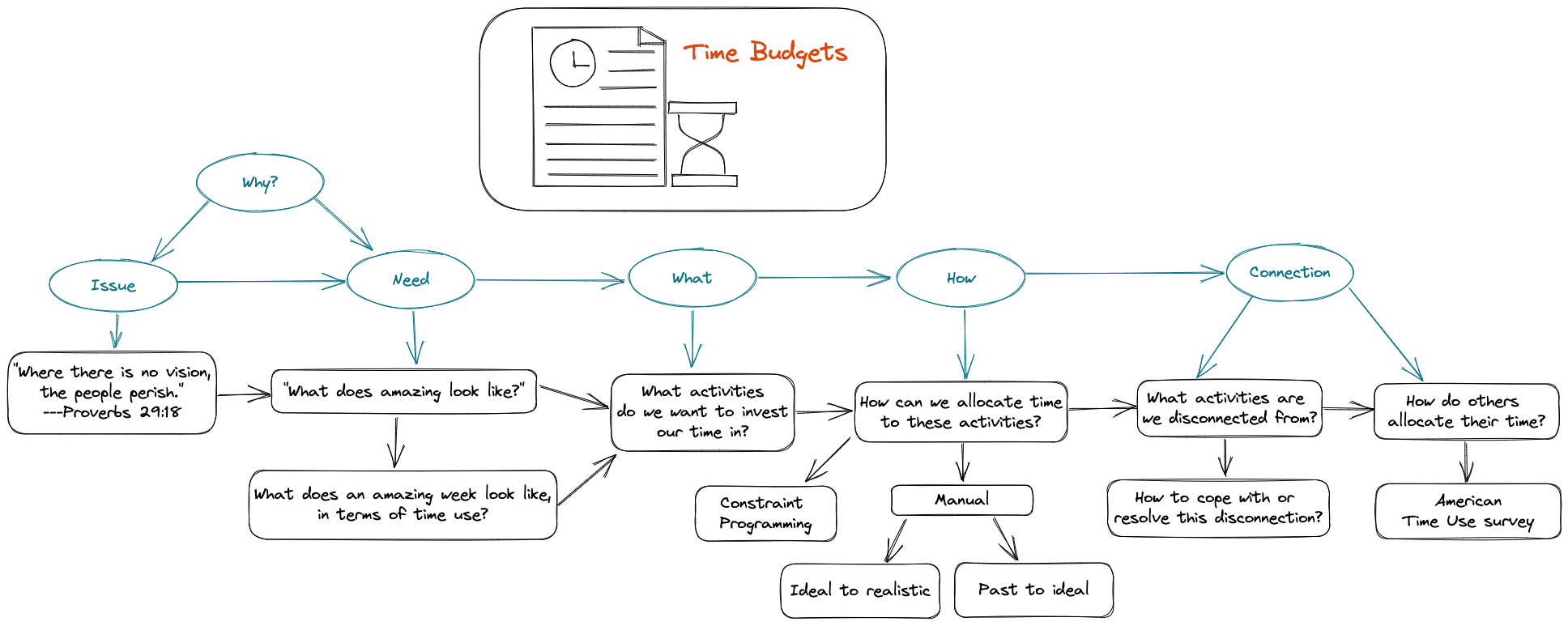

Defining amazing

Dear Young Tim,

What would amazing look like?

In Growing Pains we noted the importance of “starting with clear statements of what outcomes and functionality we want from our life’s systems.” As far as life systems go, in More Choices, Faster, we noted that our time management system is of utmost importance, because it determines how we use our scarcest resource—our time.

Putting these thoughts together, a natural question is what outcomes do we want from our time management system? Or, more practically, how do we want to spend our time? What allocation of time reflects an amazing week?

As stated rather gravely in the Bible, “where there is no vision, the people perish.” Though perhaps hyperbole, it is difficult to increase our number of amazing weeks per year, if we are not clear about what an amazing week looks like. Accordingly, to start us and keep us on a path that eventually matches our realities with our dreams, we’ll want to prioritize sketching an achievable vision of an ideal week.

Weekly canvas

Assuming we make it through the next seven days, we will have 168 hours to work with. This is the extent of our weekly canvas, on which our time-use choices express our constraints and our values. Though the hours may sound plentiful, we almost always want to do more than we have time for, and this mismatch is growing as we age. As such, it behooves us to carefully budget our time, so we can invest our time in what we care for. Additionally, we can better prepare for the consequences of the investments we chose to eschew.

Drawing activities

We can start budgeting time for an ideal week by diagramming and listing all the main activities we may want or need to spend our time on. A combination of efforts may be most useful for creating this list. For instance, we can draw from the activity categories we’ve spent time on at various points in our past. Similarly, we can include the activity categories we want to spend time on, even if we have not done so regularly before. Here, we want to include whatever activities are required in order to meet our various needs. Lastly, we can consider activity categories from resources such as the American Time Use Survey.

We found this exercise illuminating, even before allocating time to the activities. First, after arriving at a satisfyingly exhaustive list of activity categories, we listed 42 different items. This sheer number of desired activities is massive. Without explicitly and externally managing these activities, anxiety and overwhelm naturally result.

Secondly, the list was a lens through which we could view our life. We clearly saw that we had never consistently engaged in all our desired activities per week. Covering all our bases, i.e. avoiding neglect of important life systems, has never happened spontaneously. So to pay attention to all our life systems, each week, we will likely need concerted effort. Concerted effort may also be needed in order to sustainably rotate our attention between systems without any critical failures happening while we ignore some parts of our life.

Constraint optimization

With a list of desired activity categories, we can now consider constraints to be honored when allocating time across categories. For instance, we may want a minimum amount of time for specific activities. E.g., we may want at least 7 hours of sleep per night. Alternatively, we may want a minimum amount of time for any scheduled activity. Further, some activities may be constrained in the days or order in which they are are completed. And of course, we want to respect the constraints that we only have 24 hours to allocate per day and 168 hours to allocate per week.

Determining if a given scheduling problem and its constraints have a feasible solution is part of the field of constraint programming or constraint optimization. For now, we’ll start by generating time budgets manually. However, in the future, we’ll want to experiment with perhaps faster and more formal approaches to solving these problems.

So, how much time, across days of a week, per activity? To generate time allocations, we can consider at least two complementary approaches. First, we might start from an allocation in our past. Then, we make tradeoffs that respect our constraints while increasing the allocation’s desirability.

Alternatively, we can start from an allocation of time that we consider maximally appealing but unrealistic. For example, we might allocate more than 168 hours per week. Then, we can progressively edit the appealing allocation to its closest constraint-satisfying allocation according to some distance metric. Do not worry if that metric is an initially unspecified “gut feeling” about what is most similar to the maximally appealing allocation. We all have to start somewhere!

What’s missing

Our above exercises in constraint optimization will provide us with weekly time budgets that are “feasibly ideal.” They may not be all we want, but they hopefully represent the best tradeoffs we currently imagine. Looking at these aspirational budgets can teach us many lessons.

For instance, we might ask ourselves what needs are NOT met, even in our “ideal” time allocations? That is, what activity categories do we not allocate time to? And, of course, how can we prevent life system failure despite a lack of time investment in this area?

We can also ask, how do our current allocations of time differ from our ideal allocations? What activities can we feasibly do less of to reach our ideal allocations? What activities can we feasibly do more of?

Finally, we can consider relaxing some of our constraints. What constraint relaxations enable exciting allocations, as opposed to merely feasible ones? These relaxations can then serve as goals for us to work towards. We may have to endure unpleasant time allocations in the process, but we benefit long-term by unlocking amazing weeks in our future.

Connecting and comparing

As noted in the previous section, weekly time allocations facilitate comparisons over time. We can compare various points in life, using these repeated, 1-week cross-sections.

Our time budgets allow for other interesting comparisons also. For instance, the activities that we want to invest time in is a personalized basis for defining our life. Others will likely have their own overlapping but non-identical lists of desired activities. Comparing activity lists thereby shows us activities that we ignore, despite perhaps valuing.

Further, comparing time allocations can reveal when others have faster ways to meet our needs. Conversely, we better understand our loved ones’ unmet needs, based on the time they invest per activity. Such understandings can help us effectively collaborate with those we are close to.

Lastly, we can compare our time allocations to those of the “average American.” Here, we rely on tables from the American Time Use Survey. Such comparisons highlight meaningful ways in which our time use differs from others. E.g., seeing others spend more time on activities we wish to invest in nudges us to change our lived allocations.

Simultaneously, we are inspired to extend greater default compassion when we see others spending little time on activities that we deem necessary for living a “good” life. For example, only 22% of Americans engage in sports, exercise, and recreation per day. Most people are therefore set up to accumulate physical stress. In light of average time-use, we find the average person’s default state of mind immediately more understandable.

Related posts

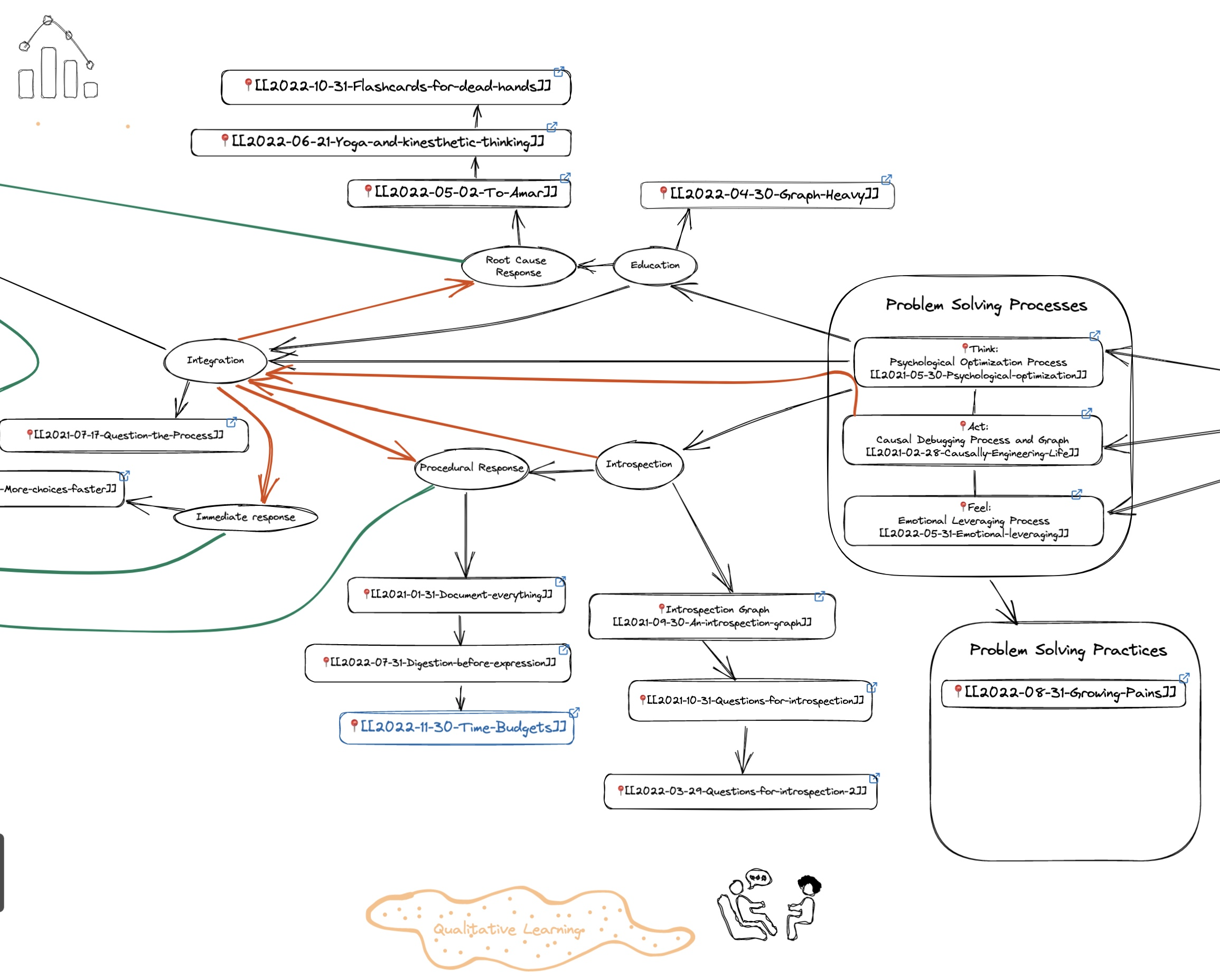

By creating weekly allocations of time, we’re changing how we decide to use our time. At the smallest level, we’re raising our awareness of how we use and how we want to use our time. At larger levels, we’re creating a tool for guiding our weekly planning efforts. In both cases, we’re procedurally changing something we’re already doing (i.e. allocating time to activities throughout a week). This classification situates our post with previous changes such as changing our journaling process or changing our blog-post creation process. Below, the subgraph of our blog’s map of contents shows this link visually.

In the future, we’ll hopefully come to generate many streaks of successfully living out our amazing weeks. Till then, may our idealized time allocations help us stay focused on the life we want to live and changes that can get us there.