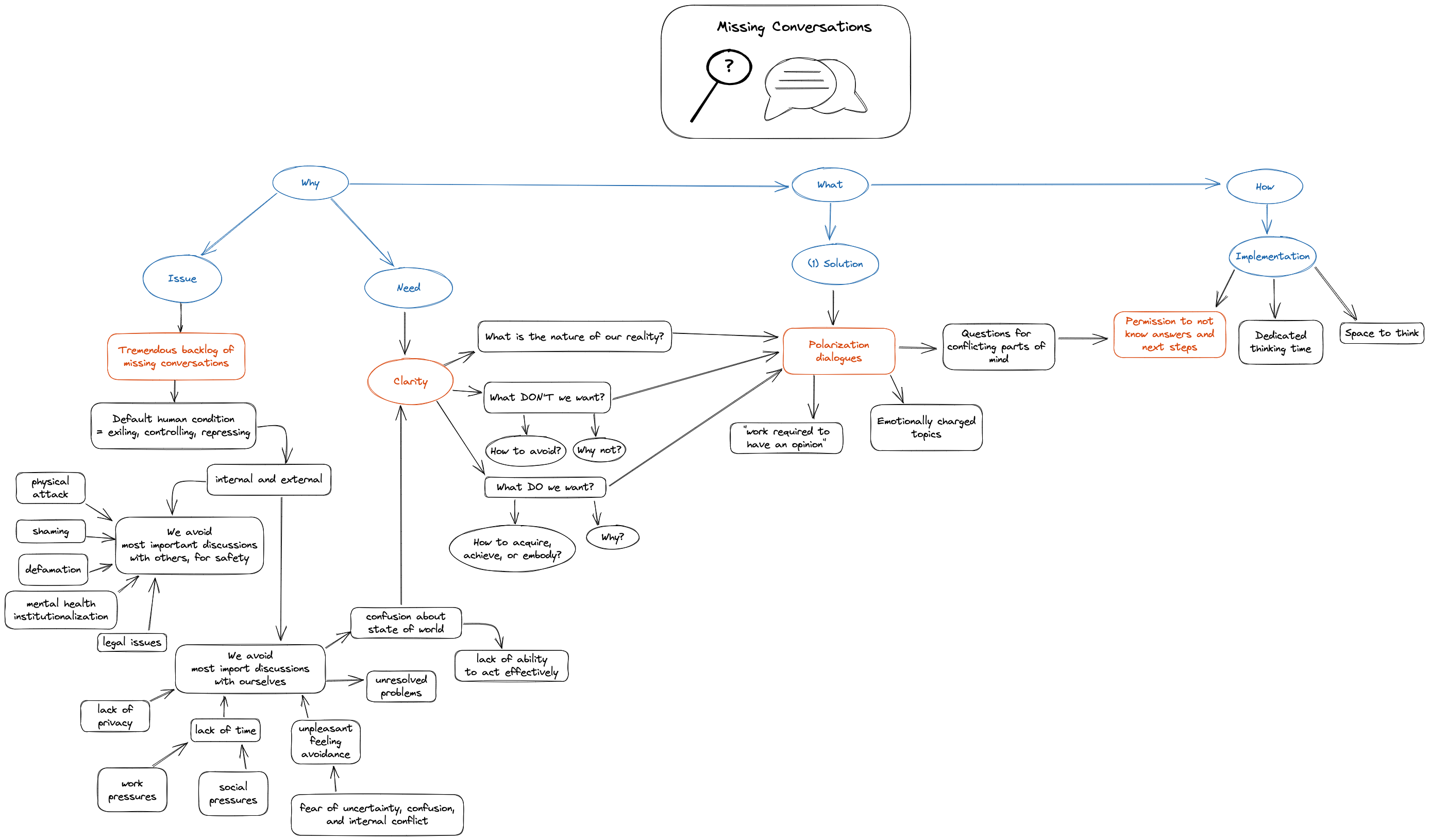

Missing conversations

On missed conversations and permission to catch-up.

Missed Conversations

TLDR

- We have many important issues and topics that we have never thought through in depth.

- Unresolved problems and confusion results from these missing conversations.

- Dialogues between conflicting parts of mind bring clarity.

- Admitting inner conflict and temporary ignorance is ultimately freeing.

Overview

The setup

Dear Young Tim,

We have an immense backlog of missing conversations. Why?

Following the Internal Family Systems model of the human psyche, we posit that the default state of people is that we:

- exile parts of our mind that carry extreme, “unaccepted,” or unpleasant thoughts, emotions, and behaviors,

- preemptively control our lives to avoid triggering the exiled parts

- and reactively repress the exiled parts of mind if we fail to avoid their triggering.

As children, the external world relates to us in this way. Think of how many kids are told to “stop crying before I give you something to cry about!” (I.e., repressed.) Accordingly, we learn at a young age that it is unsafe to openly and thoroughly discuss the most important topics in our life. If we offend the wrong people we could be physically attacked (e.g. by bullies, gang members, or parents enacting corporal punishment). Generally, speaking too candidly about problems could also lead to social attack: public shaming, reputation tarnishing, and opportunity loss. Depending on one’s precise problems, one could even lose freedom via prisons, psychiatric wards and forced medication, conservatorships, etc.

In this sense, last month’s discussion of Gendlin’s Litany is strictly to be interpreted internally. Gendlin’s Litany says that

[w]hat is true is already so.

Owning up to it doesn’t make it worse.

However, if we aggravate those who believe they benefit from weaponizing, ignoring, or hiding an issue, then speaking up about true problems can absolutely make them worse. Predation, retaliation, and retribution happen.

So, after externally relating with others, we begin to proactively and internally relate in these same exiling, controlling, and repressing ways. Our childhood and social reasoning is that it is better for us to exile, control, and repress parts of ourselves than to have others do this to us. Parallel to our external relations, we learn to avoid internally discussing, i.e. thinking, about the most important topics in our life. These are precisely those topics that activate extreme or unpleasant thoughts, emotions, or behaviors in ourselves or others.

These missing discussions about the important topics in life are then reinforced by multiple societal factors. For example, we may lack privacy: written, digital, sonic, or visual. Without ability to privately externalize our thoughts, it becomes difficult to think deeply about a topic, especially when that topic is socially rejected. Similarly, social pressures and financial pressures take our time. Without time, it is hard to calm ourselves and think continuously about anything.

Finally, even if we find time and privacy, we encounter natural tendencies to avoid unpleasant feelings. Such unpleasant feelings include the fear of uncertainty that comes with original thought. Few people enjoy being confused and experiencing internal conflict, especially without external help.

The end result of these missing conversations is a mass of unresolved problems that were never thought through and confusion about the state of our world. From this confusion comes an inability to act effectively. Without ability to act effectively, we are then unable to cope with unfolding events in our lives. This is an extremely dangerous position.

For instance, famed military strategist John Boyd explicitly stated that an aim of operations was to

Enmesh [an] adversary in an amorphous, menacing, and unpredictable world of

uncertainty, doubt, mistrust, confusion [emphasis added], disorder, fear, panic, chaos […]

so that our adversary cannot cope—while we can cope—with events as they unfold.

—“A Discourse on Winning and Losing” (p. 155)

Obviously, we wish to avoid being in such states of mind for extended periods of time.

Needs

To avoid or overcome the aforementioned confusion, we need clarity. In particular, we need to develop clarity around:

- what are we experiencing and why is it occurring?

- what do we want, why do we want it, and how do we acquire, achieve, or embody it?

- what do we NOT want, why not, and how to avoid it?

Answering these questions requires having the missing, internal conversations described in the last section. Through such thought we come to know ourselves and the world around us.

Round tables

At their core, what do such missing conversations involve? As posited in Internal Family Systems, we consider the mind to have multiple parts and as corollary—multiple sets of opinions. When we are confused, we have conflicting opinions that reflect our conflicting parts of mind. One part of us may hold a specific mental model of the world, yet another part of us recognizes this mental model’s incorrect predictions. Similarly, when we consider topics that rouse unpleasant emotions or undesired actions, we also have conflicting parts. Some parts that carry or use the unpleasant emotions and actions, and other parts seek to exile, preempt, or repress those emotions and actions.

In all cases, we gain clarity by engaging conflicting parts in dialogue about their polarization.

- What does each part believe?

- When and why were these beliefs formed?

- What is the evidence for and against each part’s beliefs?

- What are the short-term and long-term consequences of the beliefs and actions of each part?

- What are the concerns and positive intentions of each part?

- What needs does each part of mind have?

- What would have to be true to meet the needs of all parts?

The emotional problem statements outlined in Lemonade from Lemons are also a great starting point for these conversations.

In these polarization dialogues, our primary aim is not to “pick a winner.” Indeed, all parts of our mind may be mistaken. Instead, we aim to first deeply understand our experiences and only then to understand what we want and don’t want to do about these experiences. Such internal conversations between conflicting parts are the essence of both psychologist Jay Earley’s Resolving Inner Conflict and investor Charlie Munger’s work required to have an opinion.

Permissions

As noted above, our missing polarization dialogues require time and space. Beyond these basic requirements, we also need to give ourselves various permissions. We need permission:

- to admit that we have a problem or inner conflict

- to not immediately have all the answers

- and to not immediately know our next steps.

Each of these permissions may frighten us because they take us away from today’s fast-paced status quo, into realms of great uncertainty. However, through such permissions and mental exploration, we can escape ignorance and confusion about our complex reality.

For instance, in graduate school, we were terrified to give ourself these permissions in our research. Ultimately, it proved so worthwhile. From months of telling our advisor that “we don’t know” and “we’re working on it,” came an immensely satisfying understanding and productivity. Life in general asks us to “keep that same energy.”

Related posts

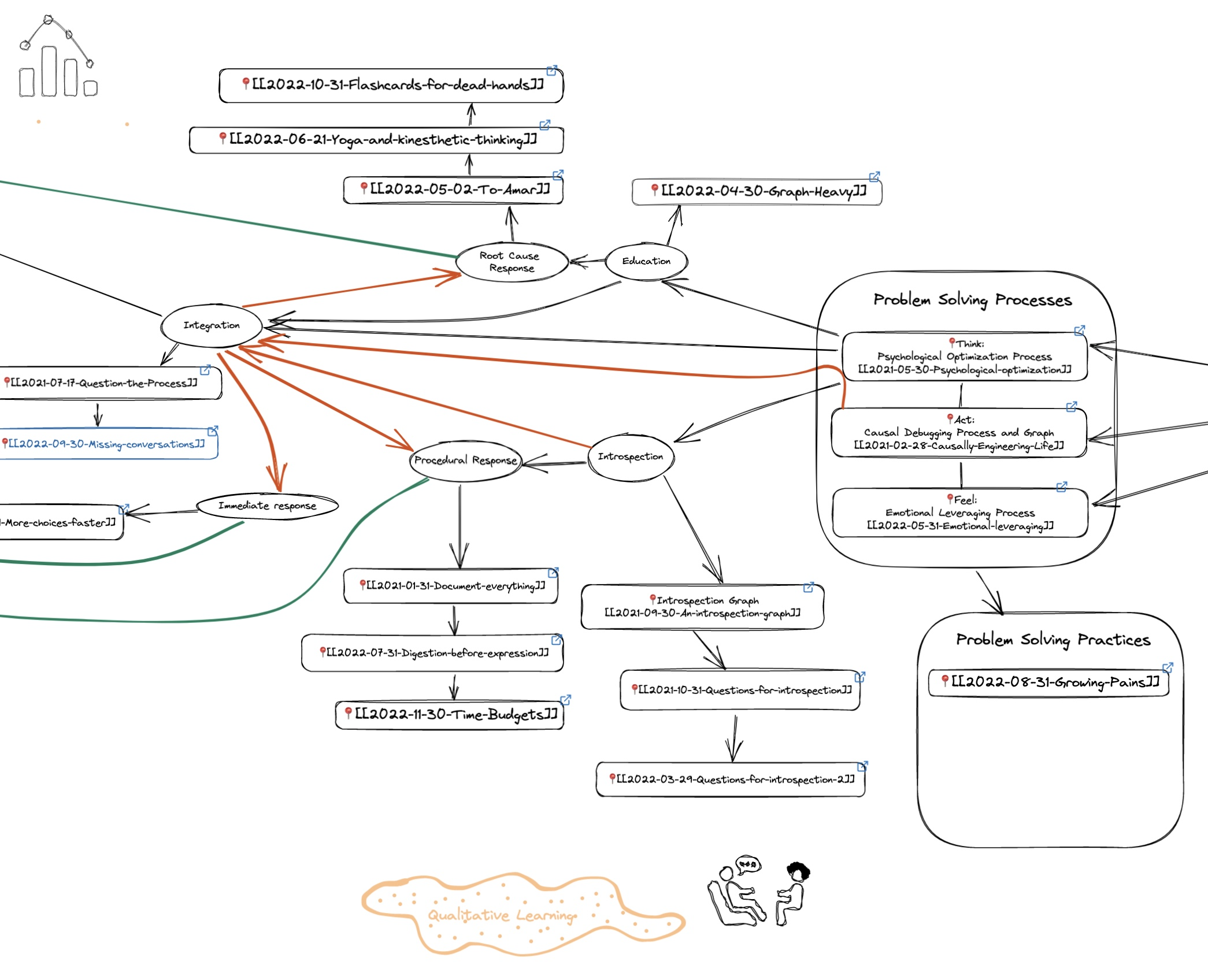

This month’s post is about holding conversations that bring together opposing parts of our mind, especially when undesired thoughts, feelings, or actions are involved. In short, this post is about integrating our various parts. This focus is reflected in the post’s position in the subgraph of our map of blog contents, below.

In today’s post we consider a “divergent” approach and set of questions for responding to problems and confusion in our lives. It is divergent in the sense that we focus more on understanding than on direct resolution of any issue. This complements the “convergent,” solution-focused approach in Question the Process. See Divergence and Convergence by Tiago Forte for more on these paired stages of creative endeavors. Here, recall that problem solving and learning are both creative processes.

Relatedly, today’s post counterbalances our thoughts in More choices, faster. There, we emphasized making decisions quickly but “only as fast as we won’t regret them.” If we have parts of mind that are conflicted over a decision, then by default some parts will regret our choices. Today’s post is about slowing down in cases of internal conflict. We aim to talk through our polarizations, rather than ignore or “push through” them. The hope is to come to understandings that reflect agreed upon truths of reality and then to make decisions that meet the needs of all our parts.

So until next time Young Tim, may you benefit from taking the time to stop and think through our many, reflexively avoided issues.